|

In February 2013, Marissa Mayer, the new CEO of Yahoo, decided to put an end to remote work at the company. In the memo, the company stated “to become the absolute best place to work, communication and collaboration will be important, so we need to be working side-by-side. That is why it is critical that we are all present in our offices.” All Yahoo employees were expected to give up any remote working arrangements and get back into the office. I had a similar experience several years ago at a company I worked for when a new executive came on board. After a short period of time, he introduced a similar policy to the one above. We were much smaller than Yahoo at the time, but had been an extremely remote friendly organization up to that point. He described his motives as much the same (though he did let slip a few times that what he wanted was to look out of his office window and be able to see everybody in his department, for whatever that is worth). So is it true? Do co-located teams truly perform better? Are communication and collaboration truly better when physically close? The conventional wisdom today seems to believe that co-located is significantly better. I’ve been personally told that all the research points to that. But having experienced both poorly performing, co-located teams as well as high performing distributed teams, I wanted to take a closer look at some of the research as well as experiences of others. Some of the ResearchThere have been a number of studies that have taken a look at co-located and remote teams. While there could still be significant research done in this area (and I look forward to more of it), there has been quite a bit written and there are some key points we can glean from these studies. How organizations support distributed project teams: Key dimensions and their impact on decision making and teamwork effectiveness In this study, the researchers looked at how organizational support impacts project teams both in the decision-making process and the overall effectiveness. Ultimately, it found three key contributors to success:

While the primary focus of this study is on the agility of distributed teams, and the difficulties presented by remote work, it also has some key takeaways for the success of distributed teams that I found helpful.

This study took a look at leadership in partially distributed teams, analyzing the different dimensions of distance such as geographic, cultural, and temporal. The key conclusion was that leaders must assist the team in bridging the distances. It took a different kind of leadership to make this happen on the teams, and ultimately took effort from leaders and team members to be effective. Supporting the development of shared understanding in distributed design teams Shared understanding is a key measure of communication effectiveness, especially on distributed teams. Reaching and maintaining shared understanding is critical, both perceived shared understanding as well as actual shared understanding. For teams to reach this level of communication and effectiveness, they need appropriate training and support. The tools that teams have access to are also very important in their ability to communicate, work on tasks, and reach a shared understanding. This study also highlights the difference between homogenous and heterogeneous teams, noting that more diverse teams (diverse in background, experience, location, culture, etc.) will require more support initially. Project Risk Differences Between Virtual and Co-Located Teams It shouldn’t be taken for granted that there are different risks in creating and managing virtual teams as opposed to co-located teams. This study looked at 55 project risk factors that other studies have identified as important to project success. Of the 55, seven were identified as greater risks for virtual teams as opposed to co-located teams. These included insufficient knowledge transfer, lack of project team cohesion, cultural or language differences, inadequate technical resources, inexperience with the company and its processes, loss of key resources, and hidden agendas. Effects of team member psychological proximity on teamwork performance Some studies have claimed that as team-member physical proximity increases, the frequency and quality of communication increases, resulting in better team performance. More recent studies have found that there is no effect of team-member proximity on team performance. The missing factor may actually be the idea of psychological proximity, which takes into account all the aspects of proximity for a team. This study analyzed the psychological proximity factors (spatial, temporal and social) and their impact on teamwork quality factors (communication, collaboration, coordination, and cohesion). Ultimately, reducing social distance helped overcome spatial and temporal distance, and was the most important factor in team quality. Social ties are incredibly important among team members. The spatial distance can be overcome with the right tools and coordination, especially when supported by the broader organization. And some sort of synchronous interaction is needed for overcoming both social and temporal distance. Summary Most studies I reviewed showed that there are hurdles to remote/distributed teams. But these challenges can be overcome with certain adjustments. We’ll take a closer look at some of those below in addition to a few examples from other teams. Some Team ExperiencesI personally have had the opportunity to work on successful satellite teams as well as high-performing distributed teams. The success of these teams wasn’t by chance. My Team At one company, I worked for several years with a highly functional, and highly distributed, development team. Our lead developer was remote as well as our UX designer. Two other team members were primarily remote, and everyone else on the team was partially remote on any given day. As the product manager, I shifted my mindset from an “in-office” focus to a remote focus. Even being in the office, we utilized the tools for effective collaboration across the entire group. It gave everyone the chance to either be present physically or dial in, whether from their desk down the hall or from their office across the country. This type of mindset was across the team. We often took time to call other team members regularly, even just to chat. This mirrored the kind of discussions that often happen sitting together. Our developers pair-programmed on the phone and shared screens regularly. Our UX designer and I regularly brainstormed and prototyped over video calls. Our team was intentional in our effort. We had to be, given our distributed group and the fact that we were working on the single most important product for the company. We made it work and were incredibly successful in developing and launching a brand new product (more on that in another post). We hadn’t read any of the studies above, but seemed to understand intuitively or from previous experience that we needed to put in the effort to bridge the gaps and create a cohesive, effective team. By the end of my time with that specific team, we had successfully launched our new application to over 100,000 students, saving the company millions of dollars and setting the stage for significant growth thereafter. InVision I’ve been interested in companies that either have remote teams, are fully remote from the start, or have transitioned to being remote. InVision is a prime example of a company that built remote work into their ethos from the beginning, and then transitioned to being fully distributed as they grew. If you’re not familiar with InVision, it is a prototyping and design tool widely used across the technology industry. I’ve been using InVision personally for many years. Since it was founded in 2011, InVision has grown to over 1,000 employees and is used by over 5 million people at thousands of companies worldwide. The benefits of being completely remote have been significant according to the founder, Clark Valberg, and CPO, Mark Frein. These benefits have included the ability to hire without geographical restrictions, saving millions by not having office space, and building a better product. InVision has been incredibly successful, and has done it with a completely remote workforce. Automattic Automattic is the company behind Wordpress, a popular content management system and site builder that is behind many websites on the internet. And it is a fully remote organization. While it also didn’t start out that way, it moved to being fully remote when it realized that it could better empower its employees by allowing them to work when and where they wanted, and after deciding that too few employees were showing up to the office anyway. Automattic now has hundreds of employees across more than 60 countries. As described in this HBR article, there are numerous lessons from Automattic, as well as some very compelling reasons why remote work has worked so well for them. One of the keys is creativity. Creativity thrives online, and allowing people to find the best way to work allows them to be far more creative than they might be otherwise. That means allowing employees to work when they are most productive, and from wherever they are most productive. Additionally, being distributed allows Automattic to hire the very best people regardless of location (a common theme among the companies I looked at who favor remote work). Automattic has been very intentional in developing its culture, and it ensures there is ample communication on teams by hiring right, providing good onboarding and tools, and then bringing people together periodically. Those steps have allowed Automattic to thrive as a remote organization, as evidenced by its growth and continued popularity of its products. Zapier Zapier has been a remote company since its founding in 2011. It has literally written a book about the subject as well. For those unfamiliar with the company, it allows a user to easily connect apps together to automate processes or accomplish any number of tasks. It essentially allows non-developers to accomplish development tasks that wouldn’t have been achievable before. Many of the lessons described so far are the ones that Zapier offers as well, as described in an interview with the CEO. The key benefits of remote work for the company have been in attracting and retaining talent, and in overall employee satisfaction. Basecamp No discussion of distributed organizations would be complete without discussing Basecamp. Its founders have long been proponents of remote work, and they have also literally written the book about working remotely. Basecamp was founded in 1999, and has had a longstanding remote-friendly environment. Though the company has stayed intentionally small, it’s longevity and growth is a testament to its values. The keys to success at Basecamp revolve around the idea of allowing employees to do deep work — limiting synchronous communication, interruptions, and meetings — and allowing employees to do their best work, however and wherever they do that. Basecamp’s style is significantly different than many other companies. It may even seem radical. But the general principles are similar to other remote companies and they’ve clearly found success in what they’re doing. Key Factors to SuccessSo what can we take away from this? How can we make our teams successful and high-performing? In order to be successful, forming and maintaining a remote or distributed team needs to be intentional, as some of the keys to success are different than co-located teams. While either structure (co-located or distributed) can be effective, both types of teams need to be designed and led with intention.

ConclusionWhen managed correctly, distributed teams perform just as well as their co-located counterparts. But therein lies the rub: you can’t simply put any team together and hope for success. It would seem that co-located teams may generally perform better because they take the path of less-resistance. There is more room for mistakes when everyone is together in an office. You may not need as strong leadership or as many tools to make co-located teams effective. The effort to communicate can be smaller and the amount of time to bridge some of the distance can potentially be shortened. That’s perfectly fine. But let’s stop claiming that one outperforms the other. With intentional leadership and design, we can create high performing distributed teams. As we’ve seen from the research and the examples above, the limiting factors to remote work are often in the effort put in rather than inherent in the nature of the team. Like what you read? Feel free to follow me over on Twitter (@kylelarryevans) or sign up for my newsletter, where I post other interesting pieces and explore a range of topics. References:

Cash, P., Dekoninck, E. & Ahmed-Kristensen, S. (2017). Supporting the development of shared understanding in distributed design teams. Journal of Engineering Design. 28(3), 147–170 Cha, M., Park, J., & Lee, J. (2014). Effects of team member psychological proximity on teamwork performance. Team Performance Management.20(1/2), 81–96 Drouin, N. (2013). How organizations support distributed project teams: Key dimensions and their impact on decision making and teamwork effectiveness. The Journal of Management Development. 32(8), 865–885 Ocker, R., Huang, H., Benbunan-Fich, R., Hiltz, S. (2009). Leadership Dynamics in Partially Distributed Teams: An Exploratory Study of the Effects of Configuration and Distance. Group Decision and Negotiation. 20(3), 273–292 Reed, A. & Knight, L. (2010). Project Risk Differences Between Virtual and Co-Located Teams. The Journal of Computer Information Systems. 51(1), 19–30 Sarker, S. & Sarker, S. (2009). Exploring Agility in Distributed Information Systems Development Teams: An Interpretive Study in an Offshoring Context. Information Systems Research. 20(3), 440–461

1 Comment

In some recent conversations I’ve had, the idea of leadership has come up numerous times. From my own leadership philosophy to the leadership (or lack thereof) of those in positions of influence, I’ve had the chance to analyze leadership from several angles. This has led me to reflect on my own views of leadership, and how I’ve implemented those principles. I wrote about the importance of establishing a leadership philosophy in my article 6 Questions for Determining Your Leadership Philosophy. As part of that process, I spent some serious time determining my own leadership philosophy and its core underlying principles. I wanted to dive deeper into it here, as a way of articulating my ideas and hopefully as a useful reference for others as they establish their own leadership philosophy. My Leadership PhilosophyGet the right people working on the right thing in the right way — and get everything else out of their way. The above statement is what I distilled from the principles below. It summarizes what I consider to be my key beliefs and how I view leadership, incorporating my core principles. Leadership for me really is about getting the right people, creating a vision for what we’re doing and helping establish the criteria and roadmap for success. And then getting things (and often yourself) out of the way. I didn’t start out with this summary though. I actually went through the process I outlined in my other article and began establishing principles that I believed were core to leadership, and my views on leadership. After several iterations, I refined my thinking to the principles below. My Leadership PrinciplesGet the right people When it comes to companies, teams, or even projects, having the right people is the first key. It’s even more important than having a vision, because without the right people, you aren’t going to reach your vision regardless of how compelling it is. In the essential book, Good to Great, Jim Collins talks about how successful leaders (Level 5 leaders as they are referred to in the book) get the right people on the bus before doing anything else. “The executives who ignited the transformations from good to great did not first figure out where to drive the bus and then get people to take it there. No, they first got the right people on the bus (and the wrong people off the bus) and then figured out where to drive it." This isn’t just for executives of large companies. It is for every team and group. The right people will make or break a product. You could have the greatest idea for a world-changing product. But without the right group, you simply won’t get there. That’s why as a leader, I think it’s crucial to find and keep the best people. I added the idea of keeping them because the best people will have lots of opportunities elsewhere. So you have to actively work to keep them within your organization. Unsurprisingly, teams that stay together longer perform better. So how do you get the right people? While this isn’t an exhaustive list, I’ve found at least a few key ideas to be critical:

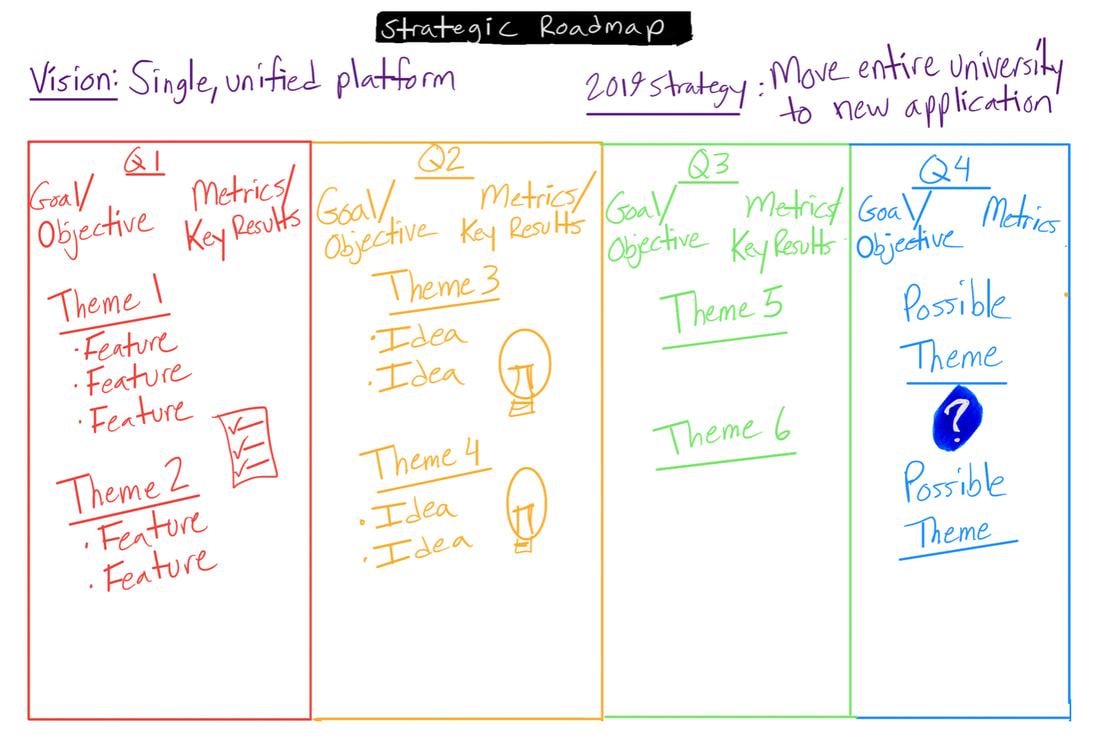

People truly are the key to success, so this principle really can’t be overemphasized. Establish Principles & Live Them “When values are clear, decisions are easy” — Walt Disney As a leader, I believe it is critical to establish personal and leadership principles, and to live by them. Leadership principles. Part of this is the exercise here — creating a leadership philosophy. Without the right principles, you won’t fully understand the actions your taking. Team principles. As a leader, it is also important to establish the principles of the team or organization. This helps guide the overall culture mentioned above, and sets the tone for autonomy. If groups can understand the overall guiding principles, they can make decisions for themselves based on those principles. Personal principles. Finally, a leader should have personal principles that they live by. This may seem like somewhat of a dated notion, but it’s something that teams, organizations, and the world need — leaders who have good fundamental principles, such as honesty and integrity, that they live by. Set The Vision “ If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.”That above quote by Antoine de Saint Exupéry (though it has a variety of different translations) really captures the essence of setting a vision. A leader shouldn’t be set on divvying up work and creating silos where each group is “optimized” for their task. Rather, a leader should inspire everyone towards a common goal. The vision is the driver, the inspiration that everyone is working towards. Jeff Bezos has put it well when he says that we should be stubborn on the vision, flexible on the details. All too often we see managers being stubborn on the details (from how we use story points to how teams run meetings) while disregarding the vision. That’s the opposite of what a leader needs to do. Define The Framework Of course, it’s not necessarily enough to paint an amazing picture of the future that we want to create. As leaders, we do need to help establish the framework for success. While a vision may be years away, we obviously need to do work now that will move us in that direction. I’ve long been a fan of Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) for this exact purpose. If you’re looking for some good books on this subject, I’d highly suggest Measure What Matters and Radical Focus, which are great reads. Creating OKRs allows you and your teams to establish what matters most (objectives) and how you're going to measure whether you’ve achieved your objectives (the key results). This allows flexibility in how the objectives are achieved, but ensures that the most important things are getting the right attention. By defining the framework, you can unleash the creativity of your teams to find the best solutions. This helps guide work toward the vision, but allows groups to be much more autonomous in how they work. Give Continuous Feedback & Recognition It is critical to give ongoing feedback to teams and team members. There is simply no other way for people to improve than to understand real-time what is working and what isn’t, so they can adjust accordingly. The idea of an annual or semi-annual performance review is probably one of the most antiquated notions at this point. And the sooner it dies, the better off we’ll all be. It amazes me that over 10 years ago, as a manager at the computer labs at BYU, my fellow managers and I had implemented a feedback system that is far superior to what many companies still use today. We actually had a mechanism for all employees to give real-time feedback to each other. That feedback could then be conveyed via managers or supervisors on a weekly basis. We were also doing a more formal review quarterly. But little of that information was new since it was being delivered continuously. Improvement was an ongoing thing. In Measure What Matters, this is the type of system advocated along with OKRs. It is called Continuous Performance Management. “To power positive business results, implement ongoing CFRs (conversations, feedback, and recognition) in concert with structured goal setting. Transparent OKRs make coaching more concrete and useful. Continuous CFRs keep day-to-day work on point and genuinely collaborative.”It’s also critical to give recognition as well. Different people will appreciate this in different ways, so it’s important to understand individuals. But everyone needs recognition. And leaders need to find ways to give that recognition. Get Everything Else Out Of The Way Finally, the last key principle is to get everything else out of the way. That often includes managers and leaders. Once you’ve got the right people on the bus, have set the vision and framework, you really need to allow them to do their thing. In Powerful, Patty McCord’s excellent book about Netflix culture (that I actually started and finished after writing most of my thoughts here), she describes one of the keys of their success as eliminating as much process and overhead as possible. Policies and structures can’t anticipate needs and opportunities. That’s why I included the quote at the beginning from Steve Jobs. It’s critical to get obstacles out of the way of great employees. And often that includes getting leaders and managers out of the way. Fundamentally, each layer of management should be in place to support those folks on the ground doing the work — not the other way around. If we find ourselves adding work because someone needs an additional report (or something to that effect), we’re doing it wrong. Leadership needs to be in support of the vision and the work, not a barrier to it. As I’ve had the chance to really think through my own philosophy and the underlying principles, it has helped me clarify my own leadership ideas as well as better understand how I expect my own leaders and managers to function. I expect that this will be subject to update as I continue to add experiences, but these underlying principles form a solid foundation from which to build, at least for me.

I’ve had multiple occasions recently to reflect on my own leadership philosophy. Not only have I been asked about it explicitly, but in several conversations with friends and others, the topic of leadership has come up with both positive and negative examples. This got me examining my leadership style and the principles that make up my overall philosophy. Reflecting on your philosophy can be a surprisingly useful exercise, because we don’t often examine many of the underlying tenets that govern our actions. But as we do reflect on it, we can begin to uncover not only our own beliefs and principles, but also the principles we value in our own leaders and managers. So What is a Leadership Philosophy?When I think of a philosophy in general, it is the set of principles and beliefs that govern our actions and direction. It is made up of many different pieces that are all intertwined, guiding us through various situations. So a leadership philosophy is made up of the core principles that govern the actions of a leader. Not only what they do, but the vision that they set and the policies they put in place to guide others. I often see “philosophy” confused for “style”. While style will be influenced by philosophy, they are not the same. Style may be the implementation of philosophy, but it is not equivalent. Additionally, style can be much more determined by situation while the underlying philosophy, though subject to reflection and revision, should not be changing situationally. It should be much more resilient and all-purpose. Why Determine Your Leadership Philosophy?Everyone has a philosophy, even if they don’t determine explicitly what it is. All of our thoughts and actions, especially when it comes to leadership, govern our direction. So even without determining or reflecting on a leadership philosophy, you have one. You just may not know exactly what it is or how it drives your decisions. By taking time to reflect (and write out) your philosophy, you can begin to have a much better understanding of the forces driving your decisions and leadership. Additionally, you can start to measure where your philosophy and implementation may not be aligned. Are there practices you currently have as a leader that don’t measure up to where you’d like to be? Determining your philosophy and reflecting on it gives you the perfect opportunity to ensure they are aligned. Or what you may need to do if they aren’t aligned. But what if you aren’t currently in a leadership or management role? For product managers reading this, hopefully you already recognize that even without managerial authority, you are in a critical leadership role. For others, I’d likely argue that you too are in positions of leadership, even if it’s not readily apparent. Regardless, most of us likely have managers and leaders in some capacity. By understanding our own leadership philosophy, we can better recognize the underlying principles guiding our managers. This is important for working with managers and fulfilling our responsibilities. But it is also critical in determining where we will work best. If your leaders and managers don’t have principles that align with your own, how can you expect to do your best work long-term? Ensuring that we determine our own philosophy and then find leaders who also align with our principles is crucial to our individual success and happiness. How to Determine a Leadership Philosophy?As I was thinking about this topic and fleshing out my own philosophy, I asked myself a series of questions that helped me begin to articulate my own philosophy. Here are some of the topics I used to help me determine my philosophy:

What is My Leadership Philosophy?As I’ve had the opportunity to reflect on the principles of leadership that I value, I’ve been able to articulate my overarching philosophy and the underlying principles. I go more in-depth on my own philosophy in my post My Leadership Philosophy & Principles, but I’ll summarize it here as well: Get the right people working on the right thing in the right way — and get everything else out of their way. The key underlying principles for my philosophy are:

Not only is this the way I try and lead, but it is how I want to be led as well. Understanding that and articulating it are critical as I continue to lead various teams and take on more leadership roles, but also in understanding the kinds of leaders I want to work with. As you begin to reflect on your own leadership philosophy, you’ll begin to set the stage not only for how you lead others, but the kind of leaders you work with. I’m convinced that if more leaders and managers would reflect on their own philosophy as well, we’d begin to see significant changes across companies and teams. So let’s all begin to be that change by understanding our own philosophies and creating the kinds of teams and organizations that everyone will admire.

Influence is probably one of the most valuable currencies as a product manager. Because you likely don’t have a lot of authority, you have to rely on your ability to understand others and help them understand your perspective and ideas. A key part to influence is having and inspiring confidence. You must first be confident in what you’re doing and what you’re proposing to do. You also have to gain the confidence of your product team, since they are relying heavily on you for the success of the overall product. You need the confidence of your stakeholders and users as well. So how do you gain confidence in yourself and inspire confidence in others? Confidence in Yourself No one will have a lot of confidence in you if you don’t have confidence in yourself. So be incredibly confident, but also incredibly self-aware. Because taken too far, you’ll lose a lot of credibility if you’re unjustly overconfident or arrogant. Gaining confidence starts with a big dose of humility. I talk a lot about this process in my post about credibility deposits. By definition, you aren’t an expert initially. But you can get there. And as a product manager, you are expected to get there. It starts with acknowledging that you have a lot to learn and then setting out to learn it. I’ve personally come into almost every product and project as somewhat of a novice. Years ago when I was working with the Money Markets and Liquidity team at Goldman Sachs, I knew very little about the products and environment. But I became an expert in the products we were offering as well as each piece of regulation and how it would impact our products. When new rules were released by the SEC, I went through nearly 1,000 pages in the course of a few days in order to review and understand the implications. The same can be said for current products I work on. But as I’ve first sought to understand everything from start to finish, I’ve been able to build up not only credibility, but confidence. As you really dive in and get out of your comfort zone, you’ll be incredibly uncomfortable for a while. But that’s what it takes. Another real key in this process is taking ownership. While the CEO analogy for product managers isn’t perfect, it is an apt comparison in terms of the knowledge you should have and the care you should take with your team, product, users, and stakeholders. Confidence from your Team As a product manager, it is critical to gain the confidence of the entire product team. You will be working together day-in and day-out. The success of everyone in that group is tied together. You succeed or fail as a team. So how can you gain the confidence of the group? Understand. Take time to understand the team. Understand how they work and who they are. Every team is different, so don’t assume that you understand until you’ve taken the time. Dive In. I’ve found that one of the best ways to gain confidence from the developers, designers, and fellow product managers you’re working with is to dive in. Head first. Get your hands dirty in any way you can. You’ll likely make some missteps, but that’s okay. That’s how you learn. One thing that I’ve found to be incredibly valuable is to really be in the trenches, even when it’s not necessarily where you add the most value. I’ve been on the late night pager duty, taking the 2am phone calls when something breaks. And even without being able to really fix anything, staying up all night until it’s resolved. Really being part of a team means being part of it all the way. Develop Technical Expertise. There is certainly a lot of debate on how technical a product manager needs to be, and it depends on the role and company. But more technical skills are rarely bad. And being able to code and understand the nuances of development go a long way in helping you gain the confidence of the other technical folks around you. Just don’t forget who the experts are. Confidence from Stakeholders Depending on the size of your organization, you may have a few key stakeholders or you may have dozens. Certainly as the size of the group increases, so does the complexity. But the principles remain the same. Again, you need to gain an in-depth understanding of each stakeholder. This time it goes beyond the understanding that you gained for your team though. Because each stakeholder will have different priorities, needs, and styles of working. You won’t necessarily be aligned completely like your development team is. As I’ve worked with a wide variety of stakeholders across different organizations, I’ve founds that I have to continually tailor my approach. Here are some key considerations: Understand the Business. As a product manager you need a broad understanding of the organization. That includes not only how your product impacts different groups, but how those groups then impact other groups as well. Without understanding the business and how everything aligns, you won’t be able to gain the confidence you need from the stakeholders in those areas. Understand the Priorities and Constraints. Each group, department, or stakeholder will have different priorities. Hopefully these all align broadly with the business, but the reality is that they may not. You need to understand this. Often there may be competing priorities in different groups that can impact your product or team. You have to also understand the constraints that your stakeholders are operating under. Often there will be budget implications, results they are responsible for, or other difficulties they have. How can you expect to sell the vision of your product or get a stakeholder on board if you don’t understand the constraints they are under. On the flip side though, by showing that you understand stakeholders priorities and constraints, you can gain a tremendous amount of confidence. For example, in one product launch that I did, we had to coordinate closely with another team in order to be successful in our release. However, they were incredibly short-staffed at the time. So working closely with the key stakeholder in that group, we were able understand their constraints, find the right level of help, and coordinate the right timing. It was a tough process. And it set us back from our target. But it was the right decision and ultimately earned us a great deal of confidence not just from that group, but from many others across the organization. Understand the Individuals. Understanding individuals means understanding who they are, how they prefer to communicate, and what level of involvement they have or need to have. This could potentially be one of the most difficult areas to navigate. And I’ve found that no matter how careful you are, you’ll likely run into trouble here (so don’t beat yourself up). Because everyone is different. Some stakeholders are very hands-on while others are largely detached. Some prefer quick summaries of highlights, others want to know all the details. Very much like tailoring roadmaps, you have to tailor communication and involvement. A word of caution as well. Don’t assume that little involvement or delegation means that the stakeholder doesn’t need to be involved. It may seem that way, but there are few things that grind a product to a halt as quickly as a stakeholder coming in from the wings because they haven’t been involved enough. Err on the side of too much communication and too much follow-up. Confidence from Users Finally, and maybe most importantly, you need to gain the confidence of your users. This is such a broad reaching topic that it could likely be many posts all on its own, especially across a product’s life cycle. But we’ll hit a few key points here. Understand your Users. You need to understand your users. Empathize with them. Know what their problems are and what they need from your product. This will not only help you deliver a great product, but will help you gain confidence along the way. Get them Involved. Do user testing early and often. Find your users or potential users and watch them use your product. Get their feedback. This is probably one of the best ways you can truly understand your users and deliver value to them. It goes beyond the metrics and gets to real understanding by watching real people really use your product. Err on Their Side. If there is ever a choice between erring on the side of the business and erring on the side of the user, err on the side of the user. Every time. For one, you won’t have a business for long without users, but it will also show how serious you are about their experience. It will build their confidence in you and what you’re doing for them. Hopefully you won’t have to make this type of call often. But you definitely don’t want to be remembered for selling out your users for the sake of your business (*cough* Facebook). Deliver Value. Ultimately it comes down to delivering value to your users. Knowing what problems they’re solving and helping them solve those problems. Once you’ve done that, you’ll already have gained the confidence of some users. Build on that value and continue to deliver. Inspiring confidence as a product manager is critical. Without it, you won’t be able to accomplish much. But as you gain confidence in yourself and inspire the confidence of your team, your stakeholders, and your users, you’ll be able to work magic. And that’s what keeps most of us here, and what makes the role of product manager so exciting.

If I could pick one thing to kill because of the problems it causes, roadmaps might very well be at the top of the list. And it's not that I don't like roadmaps, or at least the principle of product roadmaps. It's the misunderstandings that they bring. Sometimes the misinterpretation of a roadmap actually causes far more problems than the roadmap sets out to solve. Why is that? And what can we do? Purpose of a Roadmap The first thing is to really understand the purpose (or purposes) of a product roadmap. Fundamentally, a roadmap is a strategic document used to create the overarching product vision, articulating the value you're delivering to users and the business in order to gain support and alignment. I break this down into a few key categories:

All of these pieces are crucial, because a roadmap is a living document. The purpose of a roadmap isn't to create an artifact that we can refer people to or post on a page somewhere. The items above are a continual loop as we learn iterate. By creating the vision, having the right conversations with users and stakeholders, and adding the learning that we get as we progress, we can continually refine our direction and plan for the future. So Where Does This Go Wrong? The purpose of the roadmap sounds great. Who doesn't want to inspire their users and stakeholders while ensuring everyone is strategically aligned? Why would anyone want to kill that? Where does this go wrong? A roadmap is not a project plan. Far too often a roadmap gets confused for a project plan. A roadmap isn't meant to be the detailed execution of specific projects. It's not meant to commit to dates for releases or timelines for features. There is certainly a place for that level of specificity, but it isn't the roadmap, especially as we look several quarters into the future. A roadmap is not set in stone. This is probably one of the biggest problems that many of us have faced. Far too often a plan is put in place at the beginning of the year with themes or focuses for the entire year. And we get stakeholders or users who view the roadmap as a commitment to those specific items, even if we find we need to pivot along the way. This problem is exacerbated when the roadmap becomes a project plan with specific features called out far in advance and commitments to them made with dates. See this article for more about keeping a product mindset. A roadmap is not a list of features or requirements. A roadmap should be strategic. It should be focused on the vision and direction of the product, and the problems we're solving. It is about the value we're delivering, not necessarily the features. While it certainly is okay to talk about features on the roadmap, especially the near-term features that we're confident in committing too, it's important to caveat specific features with the understanding that the features are meant to solve a problem or achieve an outcome. We aren't simply delivering a wish-list of features. Key Principles Now that we're clearer on what a roadmap is and isn't, what can be done? How can we craft roadmaps that fulfill the needs of users and stakeholders while still allowing us to learn and iterate along the way? No two roadmaps need to necessarily be the same. And I won't advocate for any specific template over another here. I've used variety of different types of roadmaps and they all have benefits and drawbacks. There are a few key principles that are true of most roadmaps.

An Example What I have done with my roadmaps, and what (fortunately) seems to be becoming more and more common, is something like below (this is very simplified, but has the key ingredients): One of the key features is the focus on themes. This has been critical in aligning the product team behind a common goal. It's also incredibly useful for discussion and alignment. When we introduce the themes, it opens the door for discussion around the possibilities. For example, if the goal is to launch to a new group of users, the themes may be focused around the key items needed for that group to successfully adopt. Knowing that this new group of users needs the ability to create portfolios then becomes a theme, with potential features or ideas that we can implement in order to make that happen. The exciting thing about this structure is that it doesn't tie us down to any specific path initially. The goal is clear and the metrics are clear, but how we get there is open for discovery and experimentation. We aren't tied to a specific feature if that's not the best way to solve the problem. In the case of portfolios I mentioned above, the solutions may involve building that functionality, integrating with other applications, or finding some other way to fulfill that need for the user. A portfolio may not be the right answer at all, which is why we do discovery around the theme. Of course, as we get further down the road, our level of specificity decreases. We simply can't know a year in advance what the solution to those problems will be. Or even what the most important opportunities will be at that time. We can certainly have some ideas and don't need to be afraid to share them, but we can't tie ourselves down to a particular course so far in advance. A good roadmap helps paint the vision and strategy for the product. It outlines the key goals, often by quarter, and shows themes or opportunities that the team will be focused on. If you're interested in diving deeper into roadmaps and alternatives to the way roadmaps have been done for a long time, I'd highly suggest Product Roadmaps Relaunched, which has a lot of great tips on better ways of doing roadmaps. Ultimately a roadmap is about creating a shared understanding with our team, our users, and our stakeholders. It is not about creating a document in a specific format or with specific pieces. Part of that shared understanding needs to be that we will learn and iterate as we go. We're focused on solving problems, not releasing features. And while we may have talked earlier about a specific feature, if we can find better ways to solve problems and deliver value, many of the specifics may change as we go. Our roadmap is meant to help facilitate that understanding between groups and ensure alignment. It is about the vision and the value of what we're delivering. So hopefully more roadmaps can become helpers, rather than hindrances, in getting us to those end-goals. Roadmaps can be a critical tool for progress in product development. Even if we have a love/hate (& hate) relationship with them sometimes.

One of the biggest challenges a product manager will face (or an organization for that matter) is trying to elevate thinking and culture from a project level to a product level. Project Thinking Project thinking is fairly pervasive. Many folks, especially in software development, have spent a lot of their careers focused on projects and project management. Large organizations often have PMO departments, focused exclusively on project management. It's not surprising, because project management has been around a very long time. And we as humans tend to think in terms of projects: things we need to get done. So what is project thinking? The focus of project thinking is delivery. This could be the delivery of specific features or software, or really the delivery of anything. From aircraft to houses. And because the focus is delivery, the primary measurement is on the timeline and schedule. Project management is specifically focused on the output, and is measured by how accurately we were able to estimate the timeline beforehand and then deliver the specified output on that schedule. Success is largely defined as taking the specs of something beforehand, setting up a schedule with milestones all along they way, and then hitting those dates. Product Thinking Product thinking takes a fundamentally different approach. Rather than focusing on the output, product thinking is focused on the outcome. This is a significant shift from the mindset of project thinking. Rather than focusing on timelines and dates, we focus on the goal we want to achieve or the job to be done. Because we're focused on the outcome rather than the output, it is much more difficult to put time constraints around the delivery, at least up front. Primarily because we don't necessarily know how we're going to accomplish the goal up front. This kind of thinking can be quite the shift, especially for folks who have spent a lot of time focused on projects and project management. Many people are uncomfortable with the uncertainty of not having structured timelines and schedules that they can monitor on a regular basis. The Benefits So what are the benefits of letting go of project timelines in favor of focusing on outcomes? First of all, it is ultimately the outcome that we are driving toward, regardless of how we try and get there. The main benefit of a product mindset is that we ensure that we get to the outcome more efficiently. With a project mindset, we assume at the beginning that we already know how to achieve the desired outcome. Working from that assumption, we create a project plan and timeline full of the requirements and milestones, and then begin execution on that plan. If we're right, and what we assumed initially turns out to be the right solution, then we're in great shape. We just execute the plan and achieve the outcome. But what if we were wrong initially? What if the solution we identified isn't going to achieve the outcome we had hoped? That is where project thinking gets us into all sorts of trouble. Once we set a plan in motion, it can be very difficult, especially in larger organizations, to pivot and change. Once dates have been put in place and everyone has agreed on a plan, that is usually what sticks in everyone's minds, despite our best efforts to learn and adapt. And if we end up missing a date, it can cause incredible issues for teams and businesses. But with a product mindset, we are able to learn and adapt as we go. We aren't set on dates and milestones, but rather are focused on learning and achieving the outcome. If something doesn't work out or customers don't respond well to one thing, we can take that into account, adapt, and still work toward the outcome we had intended without blowing up a beautiful plan that is everyone's focus. Crucially, when problems arise (and don't kid yourself, they always will arise), product thinking allows us to learn and adapt, and stay focused on the outcome we're trying to achieve. In contrast, when problems arise and we're stuck in project thinking with its focus on the timeline, we will often get sucked into endless meetings trying to determine why our initial guesses were wrong and how do we get back on schedule. This ultimately leads to sacrifices in quality, work-life balance, and the outcome since we need to stay focused on delivering the output we initially agreed on (regardless if that is still the right thing to do). A Project Example We've been talking about a lot of concepts, so let's take a look at some examples to better illustrate these points. A great example of a project is the construction of a house. My wife and I built our house last year. We went through the whole process of selecting the floor plan, choosing all the finishes and details in the house, and then paying large amounts of money to get it going. When we started, our construction manager (who was absolutely excellent), gave us the estimated finish date. It was about 6 months in the future. Obviously there are many things that go into these estimates, and things often come up that throw the dates off, but since the construction of a house is a very repeatable process with defined inputs, a good construction manager can look at the plan week by week and determine when they expect to complete the work. Our house was off by about a week, which feels like a bulls-eye in my opinion. One of the trades was delayed in getting their work done, so that set things back a few days, which had some ripple effects. But that is fine. It's expected. When it comes to these types of construction projects, they are very much geared toward project management. Everyone knows what needs to be done and keeping people on schedule is a real key, especially since it wasn't just our house being worked on, but the whole development. A Product Example But does this kind of project management work everywhere? No, it doesn't. As much as we'd like to think of software development as construction, it isn't. The clearly defined plans and work don't translate to product development no matter how hard we try. While there is great comfort in well-defined timelines, that's not how we should do product development. In a product I've been working on, there is a key problem I identified and knew we needed to solve in order to continue to broaden our audience and reach additional users. The traditional approach to this would be gather the requirements, scope out the work, and then build the features. But much to the consternation of many folks at my organization, I don't take that type of typical approach. Once I understood the problem, I dove into researching solutions, from building the features to integrating third-party software. As I did this, it became apparent to me that the solution was, in fact, not to build anything. Rather than build new features or integrate someone else's software (in this case, it was a portfolio for students), the solution was to change what we were asking students to do. Rather than focus on the portfolio tool, we could simply ask them to create the portfolio pieces and then utilize whatever software solution they wanted to in order to showcase their work. The benefits to everyone would be significant. Students would be in control of their portfolio, and we wouldn't be tied to building software or using any specific vendor. We would have never come to this solution with project thinking. This solution came about because I was focused on the problem and the outcome (getting additional users on our application) rather than building the next feature. This type of result is typically the outcome of product thinking. And it can come at any point along the way. In my example above, we avoided doing any development work. But often it may take several design prototypes to figure out what will work. Or we may do small amounts of development work in learning what features will truly drive the outcome we want. No matter where in the process we learn, the key is that we are learning along the way rather than deciding on the course up-front and following a project plan. The Right Way So how do we do that? How do keep a product focus? All products and product management involve some level of project management. We have to keep things moving along and it is (unfortunately) unrealistic to assume that we can work in environment where our stakeholders and partners won't expect some dates or commitments. The key is to make commitments and project plans only at a point when we can do it with a high degree of confidence. So rather than committing to a specific path beforehand, we commit once we've validated what we're doing and have had a chance to really understand what it will take. Often that is a sprint or two into the work. That may feel really late in the process, but it is at the point when estimates and plans can actually mean something. Marty Cagan, in his book Inspired: How to Create Tech Products People Love, calls this type of commitment a "high-integrity commitment." We allow teams time to do proper discovery and research before asking for commitments. And we also need to help others realize the benefit of product thinking. There is a reason many folks ask for dates and timelines. Part of it is because of old habits. But there are times when it is necessary for business and budgets. So we need to understand what the job of the timeline is in those cases. If it is to help sell the product, we should turn the focus from specific features to the higher level story. If it is to manage risk, maybe we need to help folks understand that the real risk isn't missing a date, it's missing the mark completely on what value we're trying to deliver. At the end of the day, the whole purpose of product development is to deliver value to users and customers. Most of the time we don't know exactly what is going to deliver that value though. To think that we can come up with the right solutions up-front, sometimes a year in advance if you do annual planning and budgeting, is pretty unrealistic.

While project thinking focuses on coming up with solutions up-front and then delivering against a schedule, product thinking keeps the focus on the outcome. That involves some level of comfort with uncertainty and learning, which can be pretty hard. But if we want to get to the right outcome, and not just an on-time output, it is really the only way to work. Some teams have backlog refinement (or grooming) down to a science. Other teams, not so much. Either they don't even try, or it is a time that is more or less wasted since there is no clear direction or purpose. I've been there. We've probably all been there. And if you haven't, I suppose you can stop reading now. But for anyone who currently finds their refinement efforts lacking, here is a little something to try. And even if things are going well, maybe this could help focus you even more. As I was contemplating how to make our refinement meetings more focused, here is what I came up with. FUSE. As we examine each story in our backlog, along with the epics they belong to, I've asked the team to help think about 4 things in order to ensure each story is ready for prime time. Focused: Is each story appropriately focused? As we build out stories and descriptions and acceptance criteria, there is always the possibility that we've included too much in a given story. So asking the team to help us take a step back and make sure that the story is focused enough and doesn't need to be further broken out. Understandable: Is the story understandable? What questions remain? This is probably an area that I always need some guidance on. I understand the story since I put it into the backlog. I generally know the entire backstory as well. And the business need and the user perspective etc. But the team may not always have that full perspective. This is a great time to not only explain everything, but to also make sure all of that is captured in the story. Sized: What is the size of the story? Of course, no refinement exercise is really complete if we haven't estimated a size for a given story. Once the story is understood and broken out sufficiently, we need to size it so we have an idea where it will fit into one of our sprints. Of course, sizing is a separate topic in itself, so we'll leave that for another post. Expounded: Finally, is the story fully expounded? This ties in very nicely with it being understandable, but I think it deserves its own section. We need to make sure appropriate detail is there, and doing this jointly with the development team is crucial. It involves getting their input and including that. Expounding also extends to the epic or version as well. Our refinement meetings are great opportunities to ensure that the stories we've written include all the necessary items. Hopefully that is the case, but it's never a bad idea to pause and think again about all the stories together to ensure nothing has been overlooked. As we've implemented this "checklist" into our refinement meetings, it has vastly improved our productivity. It has given our team the ability to focus on what we need to get done and given us direction. We no longer meander through stories but have a purpose in analyzing everything. So give it a try and let me know what other practices you use to get the most out of your refinement meetings.

My Time at Goldman

A few years into my career at Goldman Sachs, I got a phone call from a recruiter for another company. This wasn't unusual, but a question he asked stuck with me. When he probed a bit about my willingness to leave and detected my hesitation at that point, he posited "So you're a Goldman guy for life, eh?" I didn't plan on being a Goldman guy for life, but I also had several things I wanted to accomplish before leaving. I wanted to establish myself as a leader within my team and within the Salt Lake office. I wanted to advance to become a vice president. I wanted ensure that I created some lasting products. Fortunately I was able to accomplish all of those things. I proposed Goldman begin to participate in the Salt Lake Corporate Games, and led the whole office in coordinating that effort for five years. It included hundreds of people each year, and over 40 teams. And each year our office was in the running to win first place. Our best finish, in my final year, was third place. A huge accomplishment. I also established myself as our team leader, taking on a mentoring and leadership role for the Salt Lake fixed income group. And in just over 5 years, I was promoted to vice president. In my final few years at Goldman, I also led the creation of multiple new products. This consisted of financial products, including three new money market mutual funds, as well as technology products, including investment tools and internal and external websites. You can learn more about my journey into product management in this post. It was after I reached many of these milestones though, that I started to think deeply about what was next for me. My Decision to Move In college, I struggled initially with deciding on a degree path. I enjoyed business and management. I seemed to have an affinity for finance. I was surprisingly adept at accounting. I loved technology. Ultimately, I settled on pursing a degree in finance since it would give me a path in a few of the areas I enjoyed. It was also a way that I could help people. Money will never go away. And people/businesses will always need help in that area. So it was decided. I would go into finance to ultimately help people achieve their goals. After nearly seven years at Goldman Sachs, I began to really think hard about what was next. There were many options for me still. I could continue in my role, taking on more projects and helping to grow the Salt Lake office. I could take a trading job in New York, and move my family out there. Or I could begin to pursue other opportunities. I also began to really evaluate what I wanted my legacy to be. A few conversations I was having with family and friends had turned my thoughts to the very long-term. When looking back on my career, what did I want to have accomplished? What mark was I going to leave? What would bring me the most joy? When I initially got into finance, it was with the intention of helping people. And while I certainly think there is a role in helping large institutions that ultimately impacts individuals, I felt too far removed from my original goal. And in my role as a product manager, I found myself the most passionate about the technology products I was creating, rather than the financial side. Moving On So with all of that in mind, I knew that the next step for me would be a technology focused role that had a significant impact on individuals. Creating the products that could improve or change lives. In order to accomplish this, I first decided that I should expand and "level up" my tech skills. So I did a coding bootcamp in the evenings and started to teach myself coding wherever I could. This of course helped in my existing role working with development teams, and set me up to better be able to move fully into the tech space. I also primarily focused my job search on the education space. I knew that there is no way to make a bigger impact on people than to help them change their own lives through education. Fortunately for me, my own decision to move on aligned with the build out of the product management organization at Western Governors University. And a great fit was made. So I left my role with Goldman Sachs in March, and straightaway started as a Senior Product Manager with WGU. With Gratitude When you're going through things in the moment, it can often be hard to be grateful. I know that is certainly the case with many things in our careers, and is certainly the case with many of my experiences at Goldman. There were some really tough times. But ultimately I'm grateful for the opportunities I had there and the things I accomplished. I'm already looking back nostalgically on a few things (though other things might take a little more time still). I learned a great many lessons in my time, and hope to continue to build on those experiences as I build the next generation of products that are going to change people's lives. When I first started in my first role out of college, multitasking was not just the norm, but the expectation. I recall getting training on a few things that I'd be doing. One task involved pulling data from a few different reports that we generated and then using that information in a handful of spreadsheets that then got put into another report. All well and good. But while the reports were being generated for that task, we switched focus to another task. As soon as a report popped open, we'd switch back to the first task. Back and forth. Add in a few other tasks during all this and hopefully you get the picture. The ability to multitask in this way was worn like a badge of honor by many people. The expectation was that everyone have the ability to switch from one thing to another to another constantly. Emails to tasks to phone calls to reports etc. Of course, I noticed this and tried my best to follow suit. After all, I was a smart individual and knew I could keep up with the best of them. Fortunately for me, I realized quickly how terrible this was. I marveled that everyone else wasn't making loads of mistakes working this way. Until I realized they were. And I was too. Any time I might have gained by switching back and forth so as to not waste a second, cost me more time going back through all my work to check for mistakes. It was a real waste. Research There has been plenty written recently about how multitasking in this fashion. Rather than gain efficiency, we actually lose it and increase risks. In the case of work, it means making mistakes on what we're doing. When it comes to something like driving and texting, the risks are even higher. The American Psychological Association has some great studies about the costs of trying to multitask and our inability to do it. There is even a great little experiment that shows how poor we really are when it comes to multitasking. Try writing a sentence and then a sequence of numbers. Now try writing one letter and switching to a number and see how well you do. Not well, I'm sure. What to Do I have the feeling that many of know this to a large degree. We know multitasking is bad. Driving and texting, Facebook and meetings, etc. But we still fall victim to it at work. At least I did, until I actively decided to kill multitasking. Here are a few of the things I did early on and try to do still. Leave the Email The main culprit I noticed early on was email. I know that not places are the same, and some organizations abuse email more than others. It wouldn't be unusual for me to receive an email or two every minute. Some requiring my attention, others not. But to stop to check email every time I received one was the biggest productivity killer there could be. So I stopped. I'd allow emails to wait until I was at a point I could shift my focus for a minute. No more being a slave to my inbox. Set Expectations This led me directly to setting expectations with everyone I worked with. I wanted to make sure they knew I'd get back to them, but not to ever expect immediate replies or answers. This took a little bit of time, but with good communication and follow-up, it works wonders. All of my colleagues knew they could depend on me to get back to them, but that I wasn't living in my inbox and may take a few minutes. Once the expectations were set, life became a lot better. Prioritize Clearly set what your priorities are going to be. What is the most important? The most urgent? What can be knocked out quickly and what might take some more time? Once you've established priorities, it's time to focus. Focus on One Task Forget about jumping back and forth between things. Focus on one thing and do it well. Even if there is a little down time in that task, like there was for me when I was generating reports, it costs much more to try and switch back and forth between tasks. By staying focused on the current task, I didn't have to try and remember where I was and what I needed to do. I saved the mental cost and mitigated the risk for me. It's impossible to multitask like we commonly think about. This doesn't mean you can't balance multiple things going on at the same time (which is the life of a product manager), but it does mean not allowing yourself to get pulled from one thing to another every few minutes. Focus on priorities and work until you get to a place where you can effectively switch tasks without losing efficiency. When it comes to multitasking, just don't.

|

AuthorMy personal musings on a variety of topics. Categories

All

Archives

January 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed