|

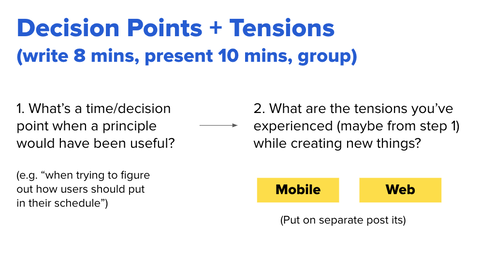

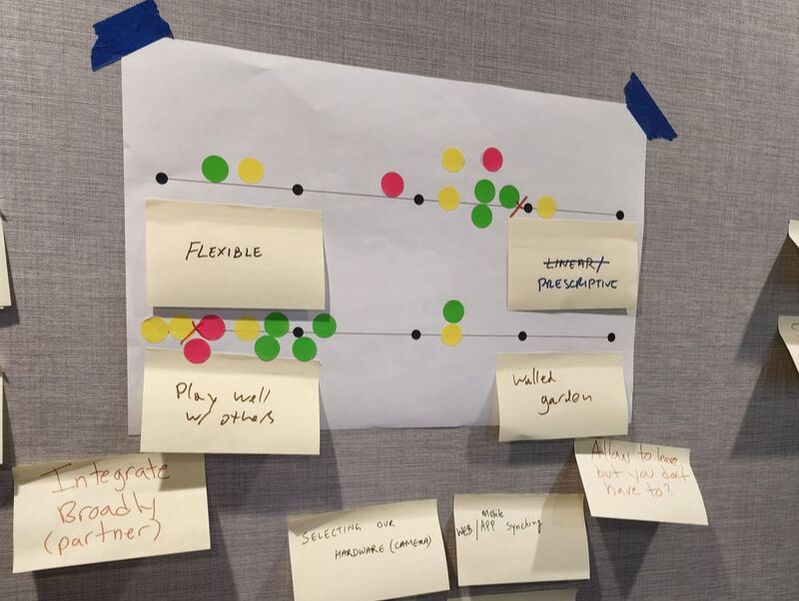

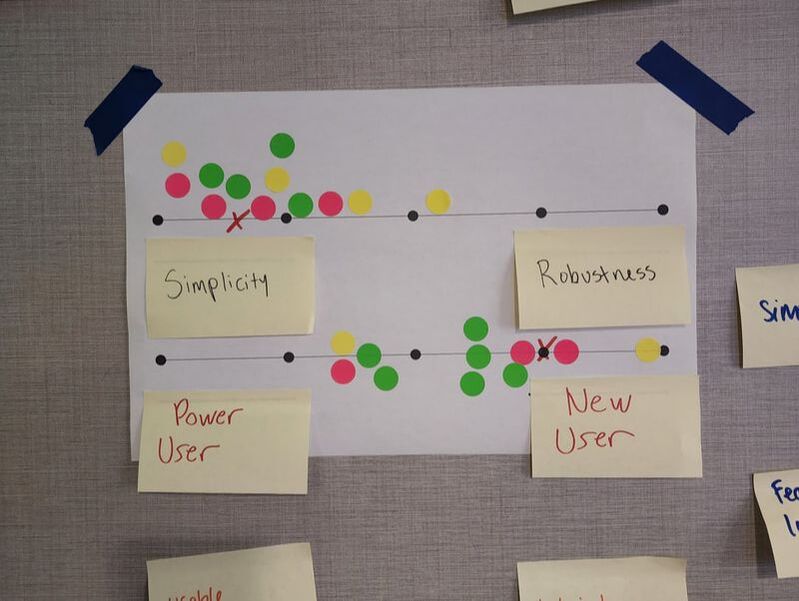

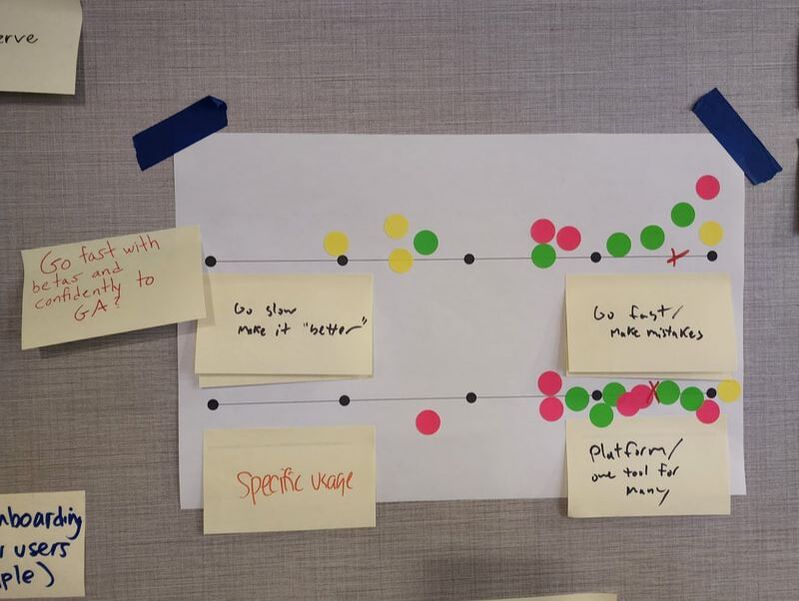

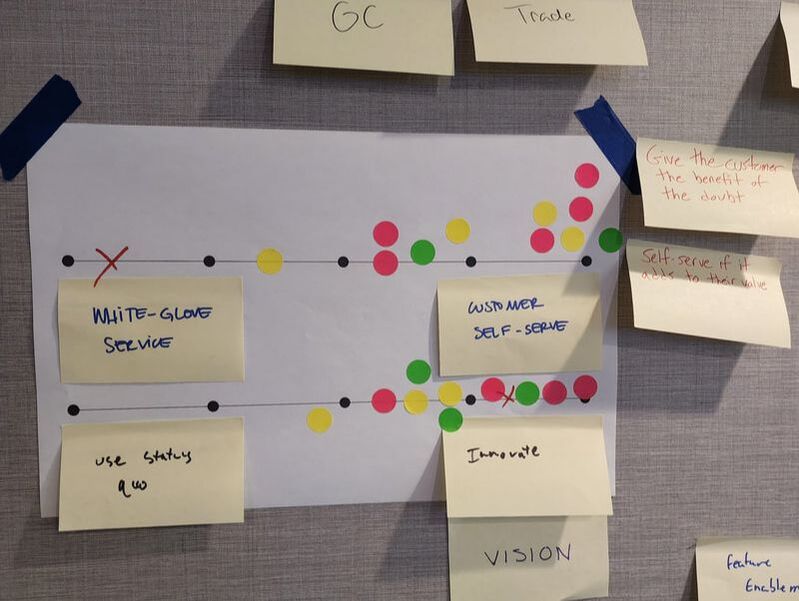

At OpenSpace, I quickly realized we needed a better way to scale our decision making and ensure that teams and product managers were empowered to make the best decisions without getting slowed down by questions or unnecessary meetings or buy-in. The main problem was that many of the decisions had long been centralized with a few executives and leaders. As the company grew, and as the product and engineering team grew, I saw that we needed a way to ensure that we could move fast without sacrificing on core principles that we all agreed on. But the key would be to agree on those key principles. First, as a product organization. Then as leadership and a broader company. So I led our team through several exercises (see the full presentation here) to determine where we were currently with our decisions, what we valued based on what we did, and where our most urgent problems were. Once we identified the problems and tensions, we had a discussion about where those problems most frequently manifested themselves. This helped generate additional ideas from our group and got us thinking more about our product areas and the places where we would benefit most from guiding principles. From there, I asked everyone to take some additional time to write out the tensions they experienced, add any that they may have missed, and put those all on sticky notes so we could begin to decide what our principles should look like. Plotting Tensions and VotingOnce everyone had a chance to write down their ideas, we put them on the wall. We took some time to group similar ideas and ensure that we all understood the notes that had been posted. Once we had our groups, we plotted opposite ideas on continuums. I wanted to force us to pick a side. For example, should our product be very simple and targeted to new users? Or should it be very advanced and created for those who are experienced. While it may be possible to have a product that can do both, it is very difficult. And when we're making product decisions, it is much better to have a clear idea for everyone, if we're going to keep our experience very simple or if we're going to be the advanced software for professionals. With that in mind, we created about 16 continuums with the tensions we wrote down. From there, I asked everyone to vote on each continuum, placing a dot where they thought we should focus. If our product should lean all the way to one side or the other, or if they were more in the middle. This gave us a plot of how everyone felt about our product and the principles we were forming as you can see: Creating Product PrinciplesOnce we had used our dots to vote, I led the team in a discussion about each of the continuums. I asked if anyone who had voted on either of the extremes wanted to give their opinion, especially in those cases when there wasn't a consensus or there was an outlier. This allowed us to begin to shape the overall principles as we discussed the thinking behind each continuum and the voting of the team. I then took each of these and crafted our product principles and tenets. We used these with leadership to begin to get their input and acceptance in order to begin implementing the ideas as well as putting them into practice and testing them out. I continued to update these principles as we got additional feedback, experimented with them, and revisited them periodically as a team. Product Principles and Tenets

0 Comments

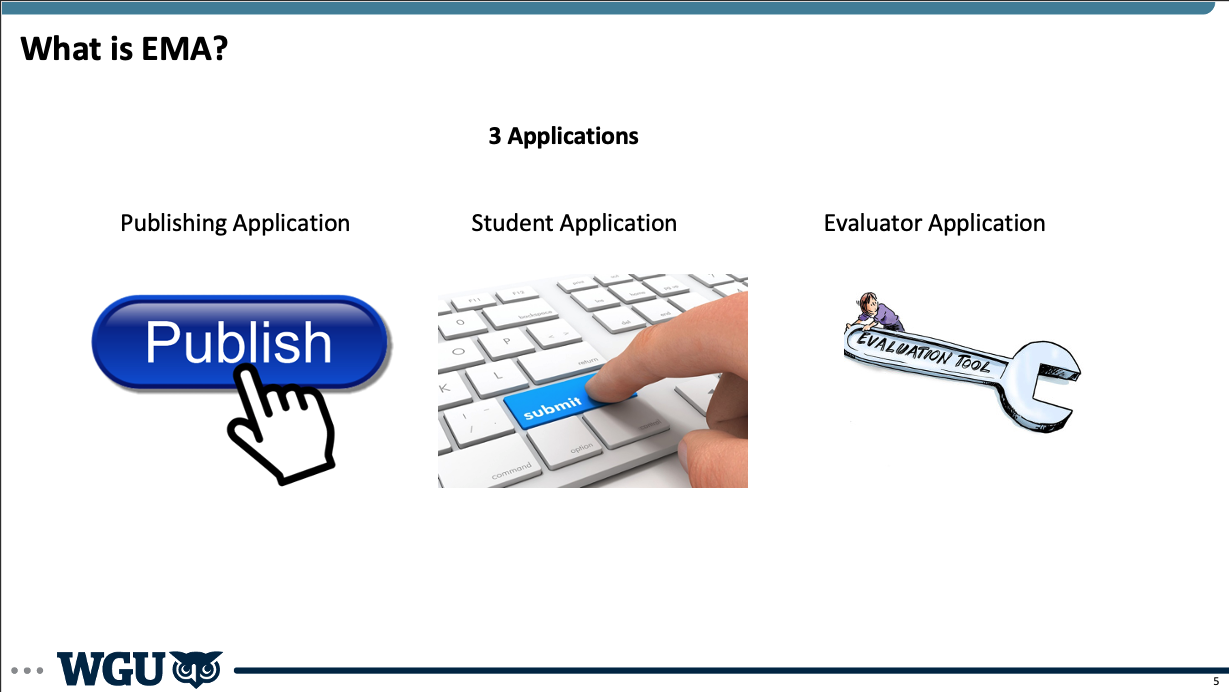

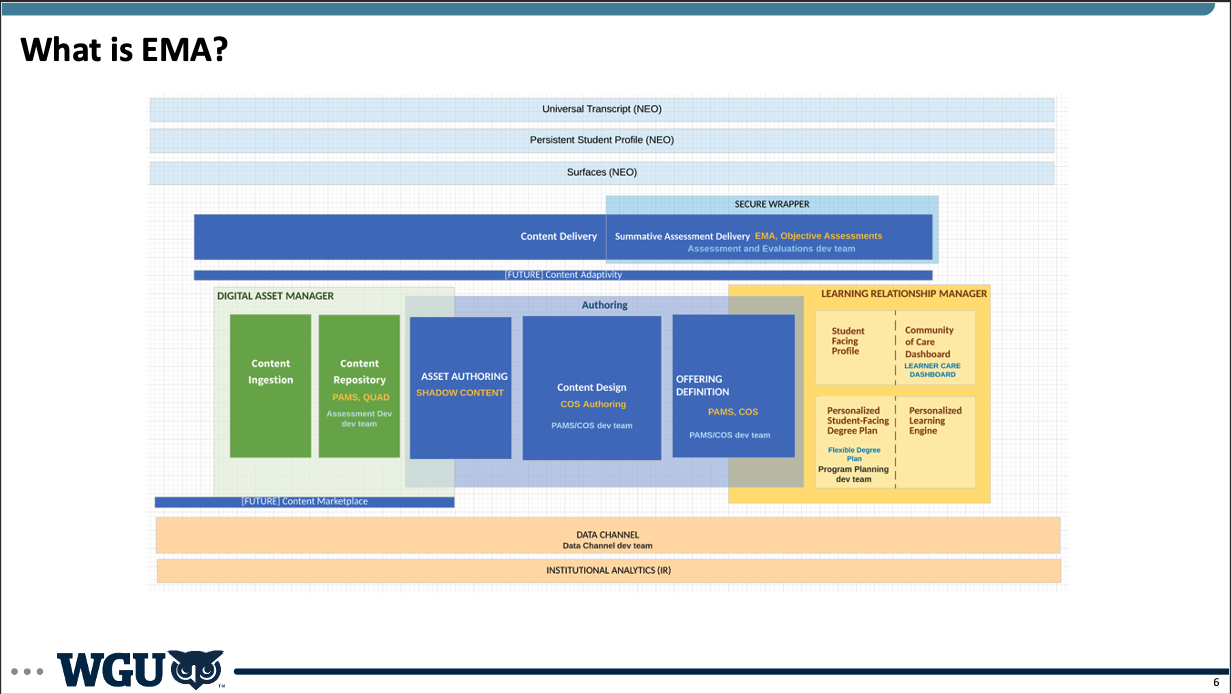

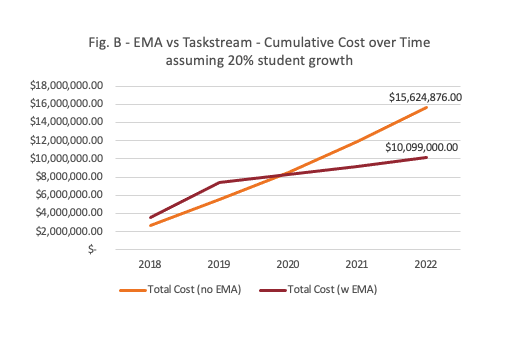

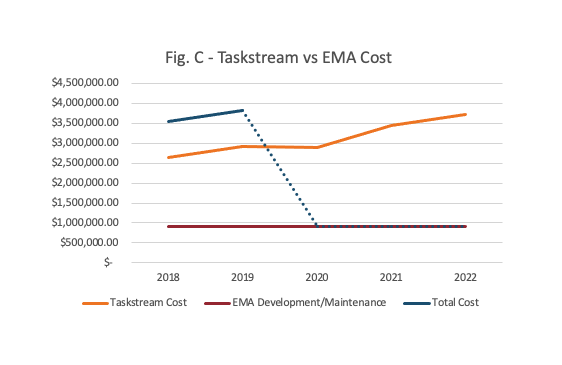

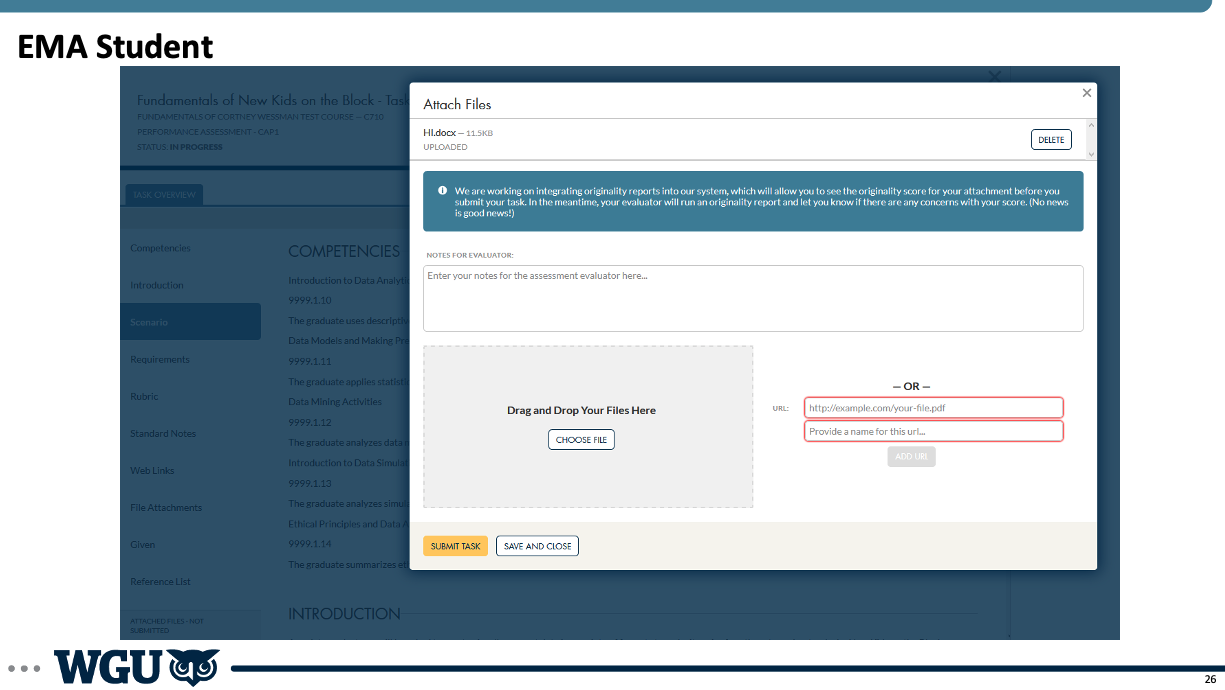

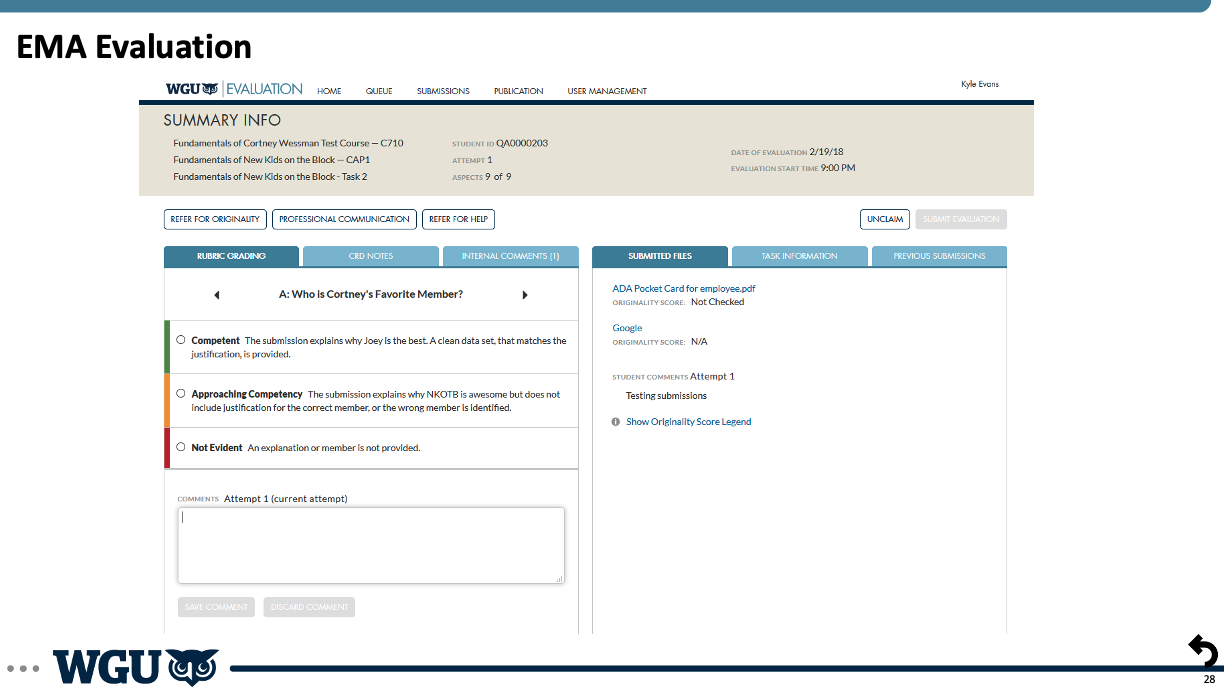

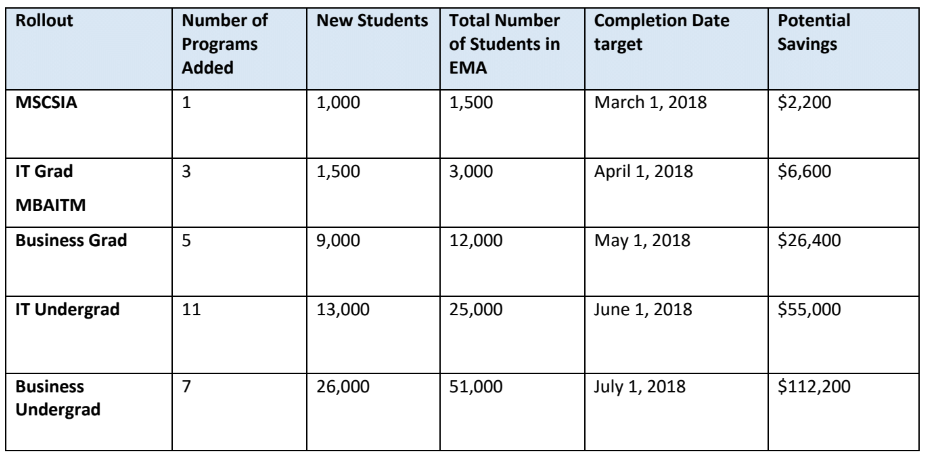

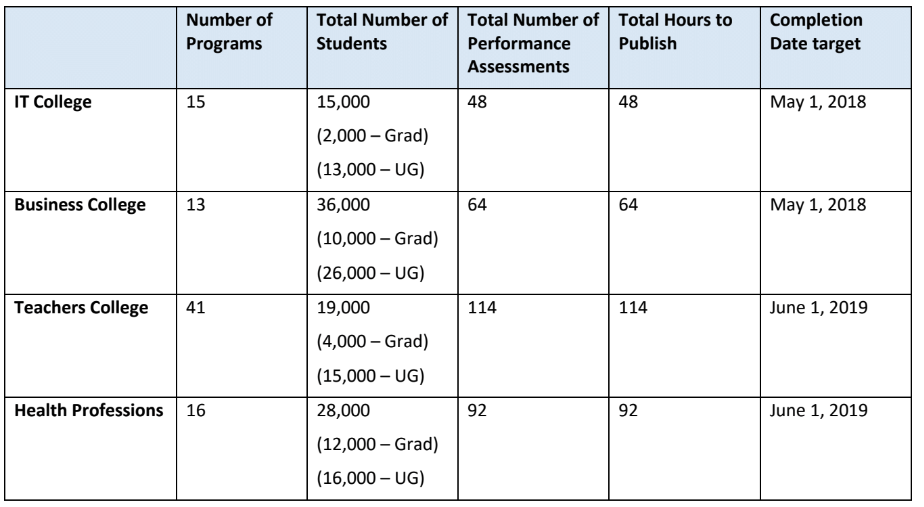

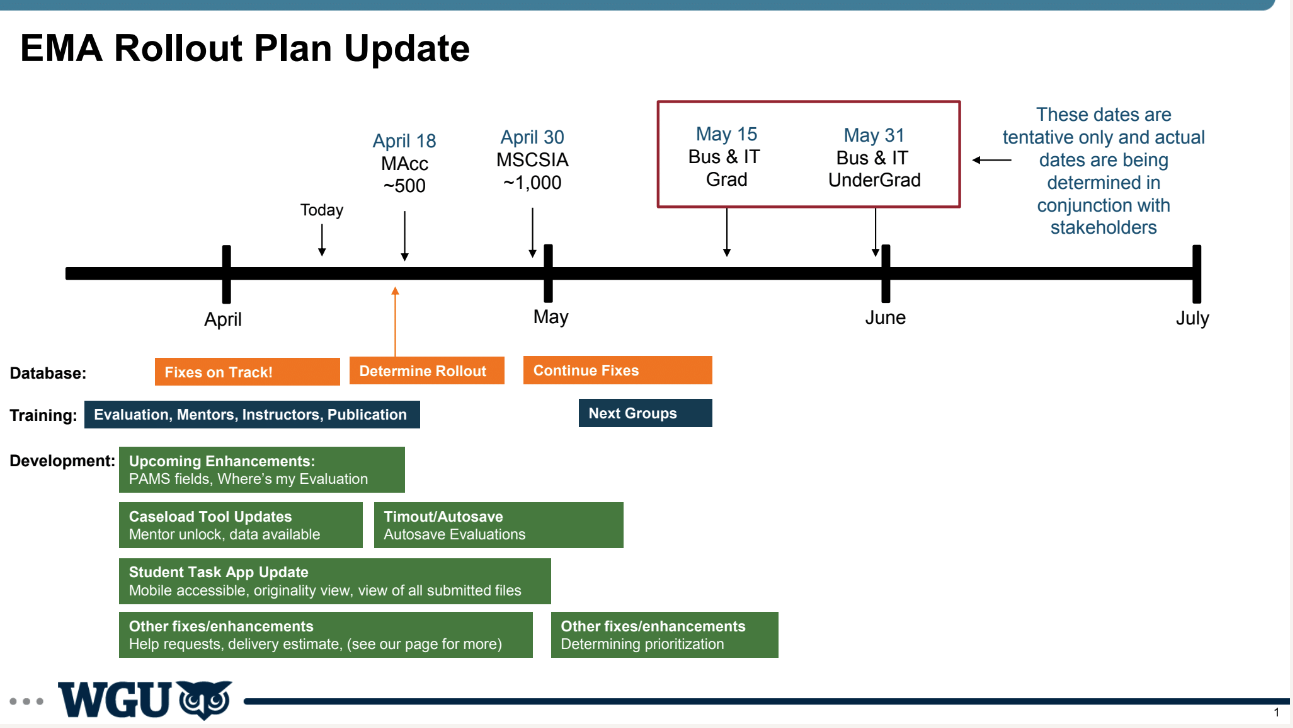

BackgroundFor years as Western Governors University grew, it outsourced much of the technology it used to third parties. This made sense initially as it focused on education. But it became clear to the university that in order to scale, it would need to bring in-house the technology. Not only to better serve its students, but because it was a different education model. The technology of higher education no longer served its needs, and it wanted to not only create software it could use itself, but could offer to other institutions who wanted to offer competency-based learning. With that in mind, WGU built out a product management organization, which I was among the first to come into and had the opportunity to help build and shape over my years there. In addition to building the product organization, I also had the opportunity to build out one of the key areas of the university: the assessment and evaluation software. For competency-based education, this is one of the most critical elements since testing knowledge is at the heart of competency. I led several teams within the Evaluation Department, and had the opportunity to imagine, design, and build out from the beginning one of the key pieces of technology for evaluation management. We affectionately called it EMA, or the Evaluation Management Application. And while the experience for users , especially students, was designed to be seamless, EMA was a massive effort that was a flagship product for WGU in many ways. EMAEMA was three applications in one. First, it was an assessment creation and publishing application. In order to have assessments available on the platform, we needed to create the ability for users, in this case faculty at WGU, to create and publish assessments to EMA. This was no small task though, since we had an entire department dedicated to developing assessments. So I had to work very closely with several teams to ensure we were creating the right tools to allow not only publishing, but different workflows for creating assessments. We started out with very basic functionality as we began, and then grew and added layers to the capabilities that EMA offered to faculty. Second, we had the student-facing portion of the application. This was fully integrated into the student portal and was seamless for students so they didn't have to go anywhere outside of WGU to find or submit their tests. This was one of the most important parts of the application early on because we wanted the student experience to be incredibly simple and intuitive from the start, even if we had to do a lot in the background to make that happen. Finally, we had the evaluation portion of the platform. This is where evaluators (a separate group of faculty) would come in to evaluate submitted exams, grade them, and send them back to students. Evaluation faculty was one of the largest faculty groups at WGU, and ensuring that we maximized their time was critical. When we began developing EMA, we started testing with just one exam, one class with 13 students, and a single evaluator. It was a good thing too, because we had to do a significant amount of work "behind the curtain" to make everything work and to learn, but with this learning we grew significantly over the subsequent months. BenefitsThere were numerous benefits to the development of EMA. We knew early on that no other solutions on the market were built for competency-based education. So we knew that building a platform specifically for this purpose would benefit our university, our faculty, our students, and the industry. We also knew if we wanted to scale both as a university and help scale competency-based education, we needed to do this. We couldn't continue to linearly pay increasing costs as we grew. This was one of the key pieces of analysis I did early on. Because we had many stakeholders who were very skeptical of the need to create development teams, dedicate significant resources, and ultimately own internally all of this technology. Finance was chief among the skeptics. So I worked on initial analysis and then ongoing updates to show our progress. DevelopmentWe developed EMA iteratively, as I mentioned before. We started out with a few students, a single evaluator, and manually doing much of the work behind the scenes to test out a lot of the processes and to make it work without doing too much development too early. We then got more colleges involved, more departments, more students, and more evaluators. And the complexity scaled significantly as we grew. I could dive into many stories of lessons learned and issues we had to overcome, but I'll touch on just a few here. Early on, we made the decision to build using a Cassandra database. Cassandra is a non-relational database. It is good for many things, and good if you have the expertise to maintain it. This was an architectural decision we made based on the expertise we had at the university, but turned out to be a mistake. A non-relational database was not right for our purposes, and our Cassandra expert soon left, leaving us without the necessary expertise to properly maintain the database. As we grew and scaled, we began to notice performance issues. As records were being deleted, it left a "tombstone". We didn't realize that we needed to clean up these tombstones in the database, which led to further problems. We also were part of a broader organizational effort to migrate to AWS. Given our lack of team expertise in non-relational databases, the need to move to AWS, the desire to better manage our application and database with a relational database, we decided that before we fully scaled up, we should move from Cassandra to Aurora on AWS. This meant a re-write of most of our application and a full migration. We had to pause all of our feature development work. I led the team on discovery to flesh out the details and estimate the scope of work, as well as worked with stakeholders to help everyone understand the need for the architectural changes and the benefits once they were done. We estimated, created the plan for work, and began. As with all projects, it took longer than our optimistic plan, but aligned with our conservative plan (or maybe with Hofstadter's Law), but we completed the move to AWS and our move to an Aurora database. Additionally, we created a seamless user experience for faculty and students. Students no longer had to submit their exams through an outside portal or vendor, but could access everything within the WGU student portal. For faculty, we created a more seamless interface that worked the way that they worked. Rather than forcing them to conform to an application, we created an application and platform that worked with them, helping them save time and mental energy, getting them through their work more quickly. LaunchThe rollout and launch of EMA to all of WGU was a multi-phased process. It involved working with every department at the university in some way, given that it touched everyone at some point. I initially had to determine which courses and programs made the most sense to focus on initially. And from there, determine how to get those assessments, students and faculty onto our platform. This involved incredible buy-in from across the university, especially as the number of courses, students, and faculty grew. I faced competing pressures as we built and launched. There was the pressure to move quickly, get our new platform out, and start to realize the savings and the UX benefits. But we also had to balance that against the changes we were asking everyone to make, especially to longstanding processes that were not easy to adjust. While we love to move quickly in technology, that isn't the case in other disciplines or departments, and we have to be conscious of that. I had to work closely with many groups, and we made lots of adjustments to our timelines and rollouts as we went. But we did hit our key goals of launching to the whole university on schedule, and eventually getting other universities onto the platform as well.

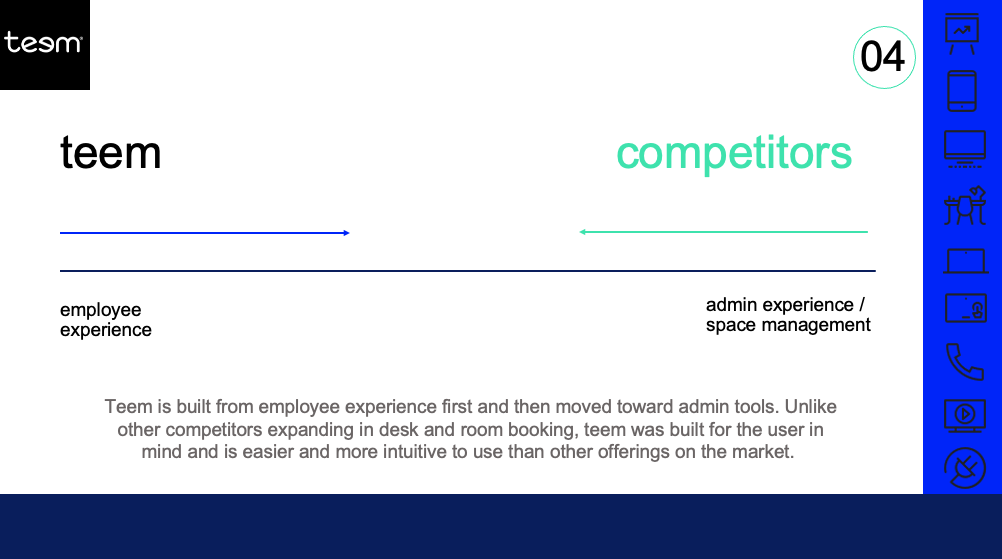

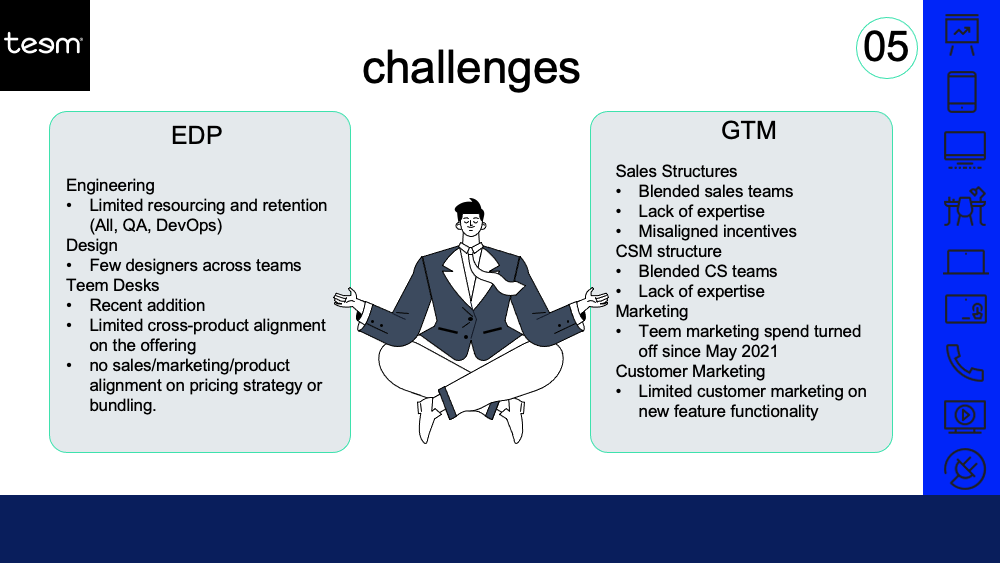

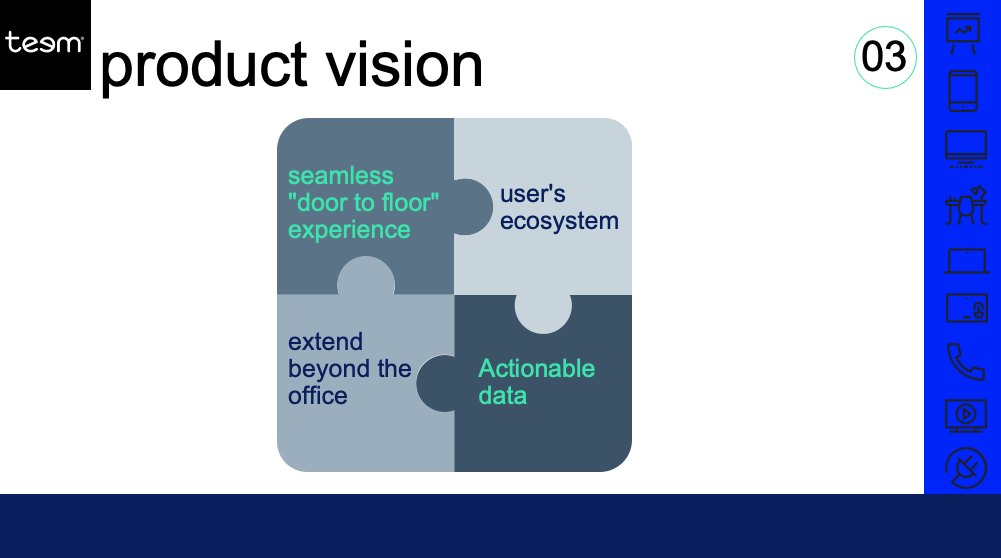

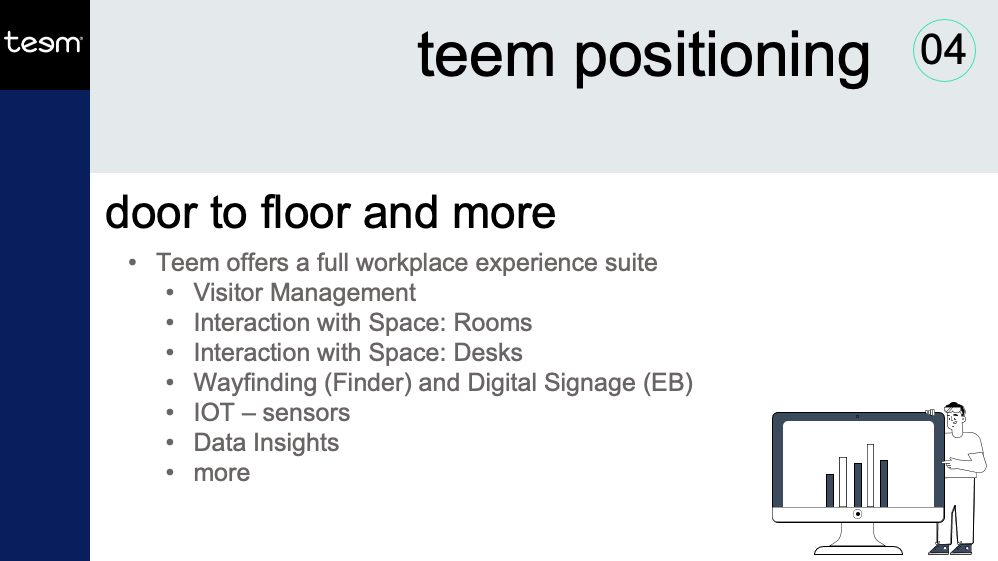

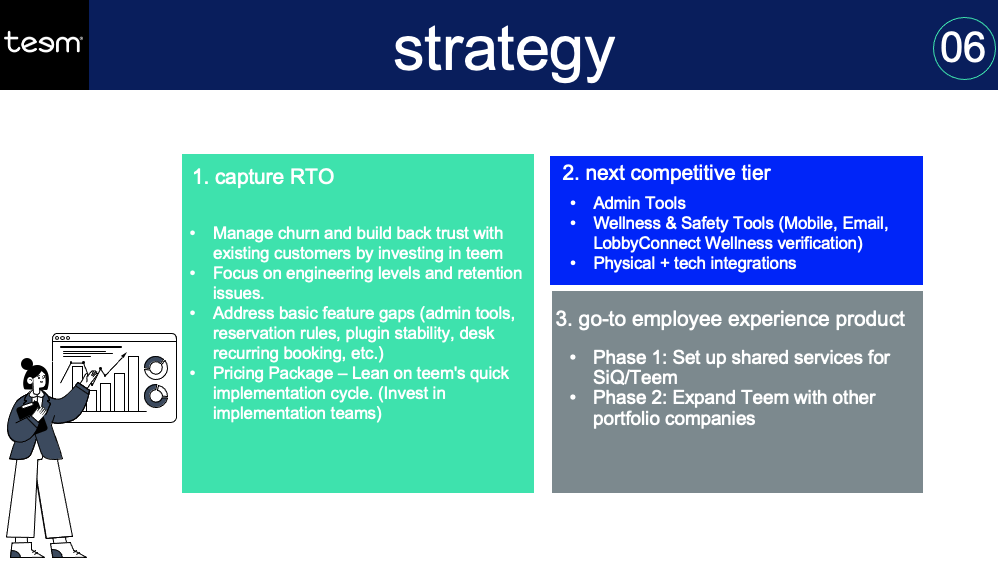

BackgroundAs Teem was acquired first by iOffice and then by SIQ, it was critical we establish a cohesive product vision and strategy to define Teem's positioning amid the market, competitors, and the portfolio of companies within our organization. So I created an analysis of user and market needs, Teem's positioning, and a vision and strategy for our product going forward. I worked closely with other members of our product, design, marketing, and engineering teams, and then presented and socialized this information more broadly to continue to gain support and help others both add to it and understand the direction we were looking to take Teem and the product. ProcessMarketFirst, it was important for us to understand the market and the context for our company and our product, especially as we were coming out of the pandemic and more companies and employees were returning to the office in some way. UsersNext, I focused on our users, their key needs in the immediate-term as well as the longer-term. It was important for us to consider the current situation, which was Covid-19 and a gradual return to offices, but also the longer-term situation which would likely see a complete mix of remote, hybrid, and in-office depending on the needs of the company and the employees. CompetitorsI also looked at the history of Teem, its place in the market, and its competition both directly as well as from other incoming solutions. Teem was built from employee experience first and then moved toward administrative tools. Unlike other competitors expanding in desk and room booking, Teem was built for the user in mind and was easier and more intuitive to use than other offerings on the market. This was an important consideration because Teem was moving more into administrative tools while companies that started out more focused on admins were moving more into the employee experience. ChallengesFinally, I reviewed the challenges that Teem was facing from a company standpoint, a product standpoint, and a market standpoint. ResultVisionOnce we had thoroughly reviewed the the market, our users, our competitors, and our company, I crafted a product vision that could address the key needs of users, utilize our strengths as a company and positioning in the market, and focus our efforts on creating the most important products, features, and experiences for the new work environment. PositioningIn addition to the product vision, I also helped craft our product positioning. This was an important aspect given that we were part of a larger group of companies within a private equity portfolio and wanted to focus on the correct positioning within that group of companies and within the broader market. StrategyFinally, in order to achieve the vision, I crafted a product and company strategy that could begin to guide us in our prioritization of existing and new product development. We needed to focus our efforts on the right things in the right way, and this was the strategy for that. With a vision and strategy in place, as well as an understanding of our positioning, we were able to really focus our development efforts and prioritize new features and products correctly. This was the beginning of a much firmer and better direction for Teem.

Temple SquareWhen you visit Salt Lake City, you'll find that Temple Square is the center of the city and everything is a grid out from it. This idea began with the Mormon church founder Joseph Smith and Brigham Young instituted it here in Salt Lake. You may also notice when you visit that the streets are very wide. This was by design. Brigham Young wanted streets wide enough so you could turn a ox team and cart around. Unfortunately, the blocks remained large rather than get divided up as was intended. The streets remained large too as everything was designed for cars as Salt Lake grew, but we’re trying to fix that and make the city more walkable. Temple Square Temple Square is much more than a religious icon. It's a collage of fascinating history, singular architecture, and gourmet dining. Temple Square in Salt Lake City is Utah's most popular tourist destination. The Salt Lake Temple is a worldwide icon of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the heart of Temple Square. The massive granite edifice was constructed in a neo-gothic style over the course of a 40-year period between 1853 and 1893. They originally used Utah sandstone for the foundation, which was buried when troops were sent out to Utah during tensions in the 1850s. When they uncovered it, they saw the sandstone had cracked, so they replaced a lot of it with granite. The Mormon temple is reserved for special ceremonies, sacraments, and rituals for members of the Mormon church, so only they are allowed in. But since it is being renovated now, anyone will be allowed to tour it before it begins to be used again when the renovations are complete Salt Lake Tabernacle Home of the world-famous Mormon Tabernacle Choir, the Tabernacle, located just north of the Assembly Hall, is an architectural and acoustic wonder. The famous organ at the front of the Tabernacle contains 11,623 pipes, making it one of the largest and richest-sounding organs in the world, and the building was constructed so that even the drop of a pin at the front of the building can be heard throughout the building. The Tabernacle is usually open daily for tours. In addition, the public is welcome to attend choir rehearsals on Thursday evenings and the Music and the Spoken Word broadcasts on Sunday mornings at 9:30 am. Assembly Hall Construction began in 1877 and completed in 1882. It was used as a church and gathering place for members of the Mormon church. Now it is a place for free concerts Conference Center This building contains a 21,000-seat auditorium and an 850-seat theater. It also houses an array of artworks that tell about scripture stories, Church teachings and organization, etc. Free, guided tours of the Conference Center are available daily from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m, and tours of the beautiful rooftop gardens are available April through October. Between Memorial Day and Labor Day, and during the month of December. Hotel Utah It was once the premier hotel in Utah. As Utah grew, people knew they needed a nice hotel for everyone coming into the city, especially with all the new wealth. It opened in 1911 and hosted most major Utah events for the following 76 years. It originally had a bar and served alcohol, but the hotel closed in 1987 and reopened as an event center and restaurant owned by the Mormon church as the Joseph Smith Memorial Building. And you definitely can’t get a drink there now. But it does have some great views and a great restaurant at the top as well as banquet halls for parties and events. It is currently closed for renovation as well. Beehive House The Beehive House was built in 1854 as the primary residence of Brigham Young as the first territorial governor of Utah and President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was primarily a residential home, but was also used to entertain guests and dignitaries, including President Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Mark Twain. Lion House The Lion house was also a family home of Brigham Young. Brigham Young was married to 56 women, but only 27 were part of his households, and he only had children with 16 of his wives, which ranged between the ages of 15 and 69 when he married them. He had either 56 or 57 children depending on the source, which is roughly an average of 3.5 children per wife, which was below the average at the time. Arena and Gateway

Theatre and Salt Palace

Main Street / Whiskey Street

Downtown FavoritesPretty Bird Hot Chicken - Right behind on Regent Street is Pretty Bird Hot Chicken, an amazing chicken sandwich shop. It is a local restaurant and will be the best chicken sandwich you’ll ever have. Red Rock Brewery - Great brew pub and restaurant. In a cool, old building, it has a great atmosphere, good food, and good drinks. Hotel Monaco and Bambara - The building was constructed in 1923 and was originally a bank. It was converted to Hotel Monaco in 1999. Bambara is a favorite downtown spot with a great atmosphere for lunch, dinner, or a nightcap. Market Street Grill - Great local seafood and steak restaurant Takashi - One of the best sushi restaurants in the valley Squatters Pub - Utah has a 100 year history of strict alcohol laws as you may be aware of, but as some of those started to loosen in the 1980s, brew pubs began to open. One of the first was Squatters. Good Cobb Salad and onion rings. Christopher’s Prime + Sonoma - A locally sourced grill and bar. Great selection of steak and seafood. Apollo Burger or Crown Burger - Both Utah originals. Grab a pastrami burger and don't forget the fry sauce. Pago - Great local restaurant with locally sourced food. Has a downtown location and another one a little further away. Whiskey Street - Fun bar for drinks and apps. Right on main street, so easy to walk to. Other Local FavoritesSawadee - One of my favorite Thai restaurants in Salt Lake

Red Iguana - The best Mexican food in Utah in my opinion. You'll need to drive to get to the restaurant (either one or two), but it is worth it. If you can't drive out there, they have put a Taste of Red Iguana in City Creek, so you can try it there as well. The Copper Onion - Nice dinner restaurant that is a little outside of downtown. Also does brunches on the weekend. Feels nice but comfortable. Capitol Hill

Mining, Railroads, and Growth

Early Utah History

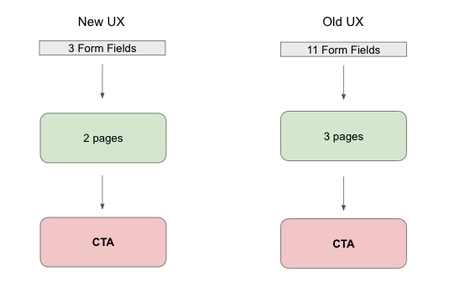

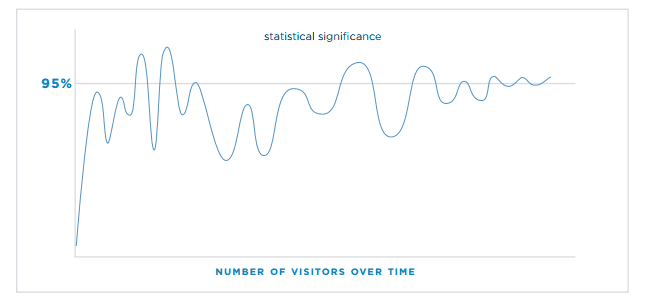

At Clearlink, our product organization worked closely not only with the broader organization, but also worked closely with marketing partners in order to build new products, test ideas, and drive better business outcomes. As part of this, we were often running A/B tests of marketing changes. We worked with our partners to create new marketing copy and then test out the changes over certain periods of time to see what images or phrases would work best for their sites. But as I helped build out the product and UX organization, we wanted to expand from just running A/B tests on copy and images and use the same methodologies to experiment with user flows and the actual experience of the users on the sites. This was a bigger deal, both for our partners and for our teams because it involved more work to create the changes, as well as more buy-in to allow us to run experiments not just with language or images, but with the actual experience of users. But we were adamant we could improve the user experience of their sites, helping to improve traffic and drive additional conversions. So we designed and created a new user flow for one of the sites that we targeted first. This was an online retail site that gathered information and then moved people to either sign up online or call a number to sign up. Our hypothesis was that we could simplify the user flow, eliminating over two-thirds of the steps to get the user from first action to a purchasing decision, and increase conversions by requiring less of the potential customers. I worked closely with our partner to overcome a number of obstacles and concerns, and we created prototypes, reviewed designs, and prepared stakeholders for the changes we were creating. (This may seem like overkill for some good UX changes, but we were dealing with a large telecommunications company that didn't like change and didn't like to move fast or try new things, hence the need to really get everyone on board) Launching the TestWe ran a 2 week test of our changes versus the unchanged site. We randomly assigned visitors to one of the two sites, but also tracked unique users and attempted to give them the same experience if left and returned. This specific site traditionally got thousands of visitors over the timeframe we were targeting, so we were confident in getting enough traffic for a meaningful result. We used many of the same targets for other A/B tests that we ran for other marketing purposes, including a full testing period and appropriate confidence intervals to test for statistical significance. It's important to run a test for a full length of time, because stopping a test short can lead to noisy results or incorrect conclusions. This was certainly a temptation, especially with a partner who had reservations about so many changes and also would want to stop using one of the sites as quickly as possible if the other was showing significant good results comparatively. As you can see from this image, there is noise in data, and stopping an A/B test early can lead to making the wrong decision, which is something we reminded everyone of as we tested. The ResultsThe results of our UX changes were even better than we expected. We had set a p-value of 0.05, but got a p-value of 0.01, suggesting statistical significance beyond random chance as we saw conversions almost double over the time period on our site with the UX enhancements versus the original site.

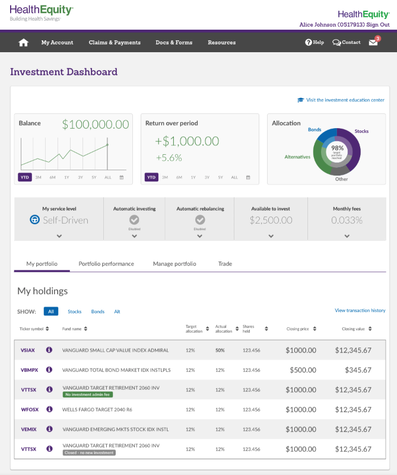

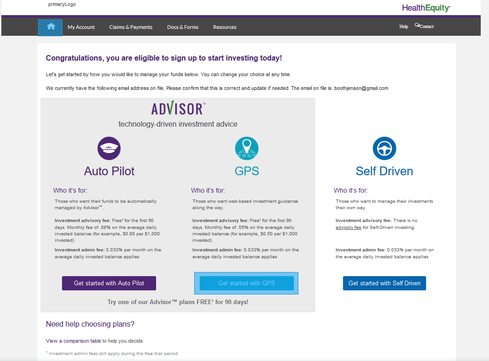

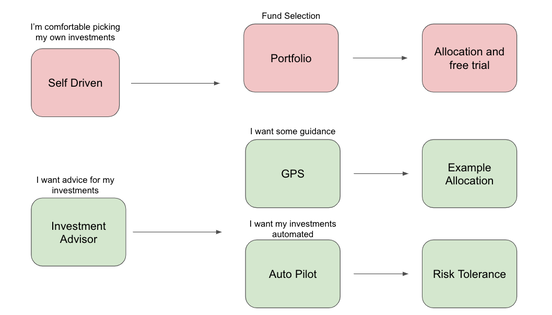

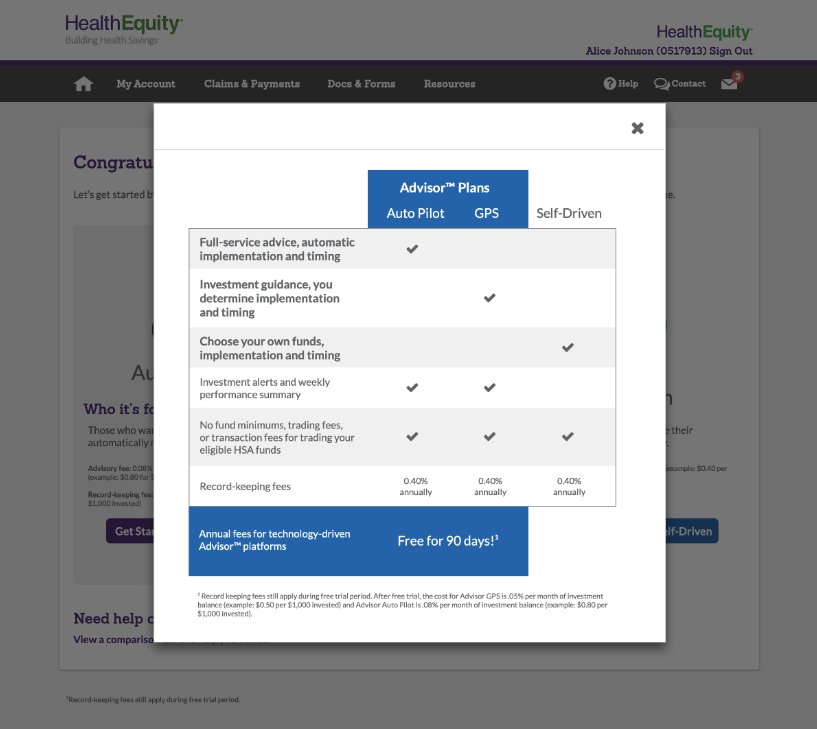

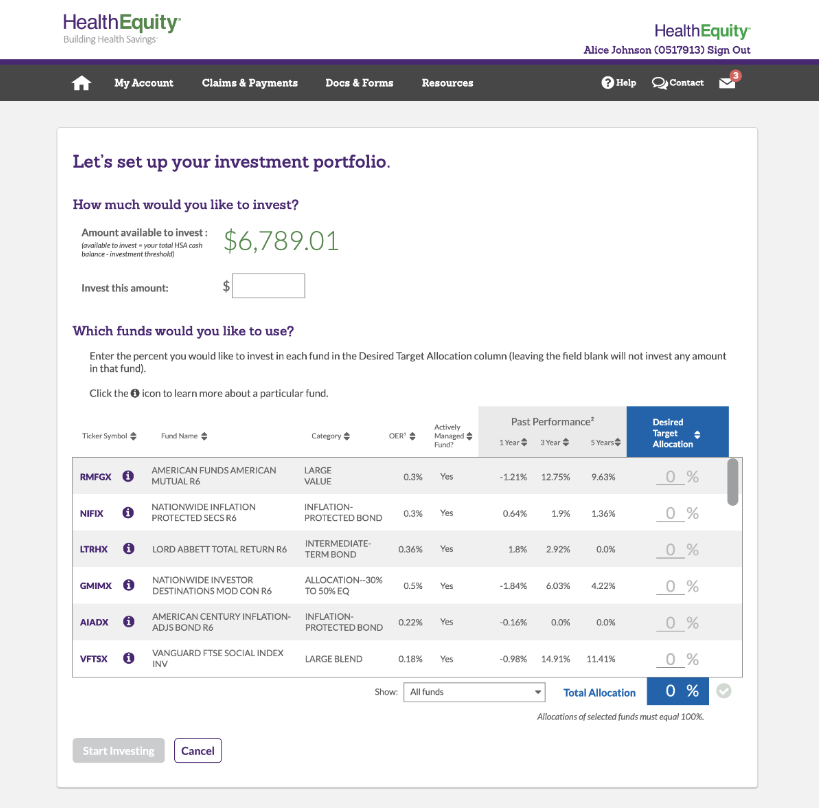

This was a validation not only of the changes we made, the designs we created, and the work we did to get the partner on board with the test, but also more broadly validated the work I was doing within the product and UX organization. UX changes--designing better experiences and not just nicer pictures or better wording--has a significant impact on the overall user experience and ultimately the business value. I continued to use this as an example of the value of product and UX as we worked internally as well as with other partners, to help everyone understand how and why we can focus on the users and why taking time to design the whole experience adds significant value. I believe wholeheartedly in the power of quantitative and qualitative data. I often view it as a funnel where quantitative data and point us to issues or opportunities, and qualitative data helps us dive deeper in order to create compelling solutions. BackgroundOnce HealthEquity HSA members have saved a certain amount of money in their health savings accounts, they can invest the additional or excess funds from their HSA in a variety of mutual funds. As a product team, we knew from our analytics that a significant number of users didn't complete the investment onboarding and that we needed to fix this to grow our investment users and help all members maximize the benefits of their HSA. ProcessInvestment Platform at HealthEquityI used qualitative and quantitative data to create a significantly better investment onboarding experience at HealthEquity. When I came into the role, we knew that the investment experience was clunky and outdated. But didn’t know much beyond that. The company wanted to make it better, but didn’t know where to focus, hence my role. I started by analyzing the user flow from the instrumentation we had (which thankfully, was pretty good). I noticed a couple things, like a 50% drop of at one point in the onboarding process, and another point where around 3/4 of the users who made it there fell out. That gave me great context for diving deeper. I started by watching actual users go through the investment onboarding flow without interfering at all. I wanted see and understand the process from their point of view. Like the data showed, there were drop-offs at a choice between several investment options, another at the selection of investments, and finally toward the end before completing. So I started to ask “why”. After a series of interviews, I had a much better understanding of the problems user were facing. This included being overwhelmed by the choices, unfamiliarity with investing, or just fear of pulling the trigger. But I didn’t stop there. With that understanding, I worked with our UX team to create new user flows. We mocked them up and I put them all into Invision so we could test them with users. I went out and spent several days onsite with customers having them walk through our mockups. We learned that we had made the process better, but still hadn’t solved all the issues. One key problem was that we presented users with too many choices too early. Specifically, we asked them to pick between three options for investment guidance right at the beginning: Auto Pilot, GPS, or Self Driven investment. SolutionsAt that point I had the epiphany to radically change the flow even further. Rather than having three options at the beginning, causing users to segment themselves into specific buckets before they fully understood their preferences or own investment needs, we needed to guide them. This meant simplifying the choices at each step, and segmenting users along the way to guide them through the process and change the pricing structure. This required buy-in from a number of groups, including our investment team, sales, marketing, etc. So I made the pitch and showed them the data from our current users as well as the feedback from interviews. This helped everyone understand the need for pricing changes and a simplified process. And we moved forward with it, doing a few more testing sessions and then releasing the first iteration. We moved to simplify to investment flow as shown below. Rather than multiple screens and steps, we consolidated the decisions and guided users along the right path. ResultWe saw an initial increase of adoption of 400% as users were able to more easily complete the onboarding flow. We also saw an initial increase of initial investments of 25% as fewer users dropped out of the investment process and got their HSAs invested.

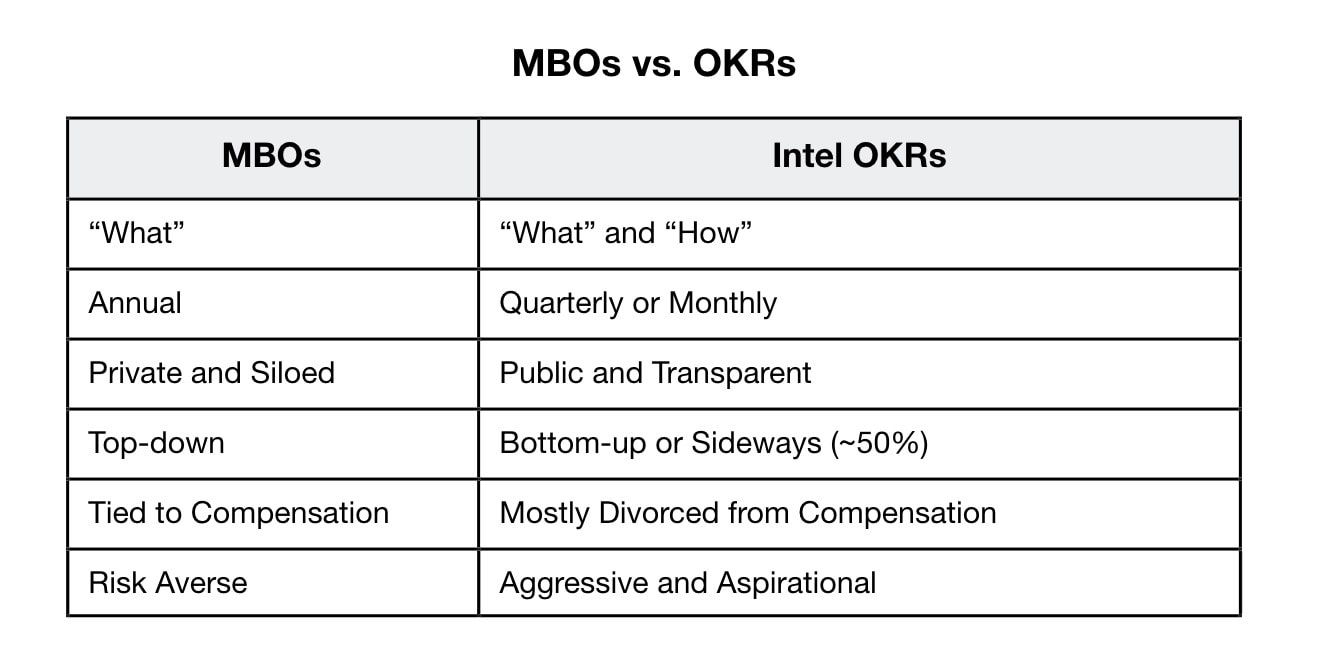

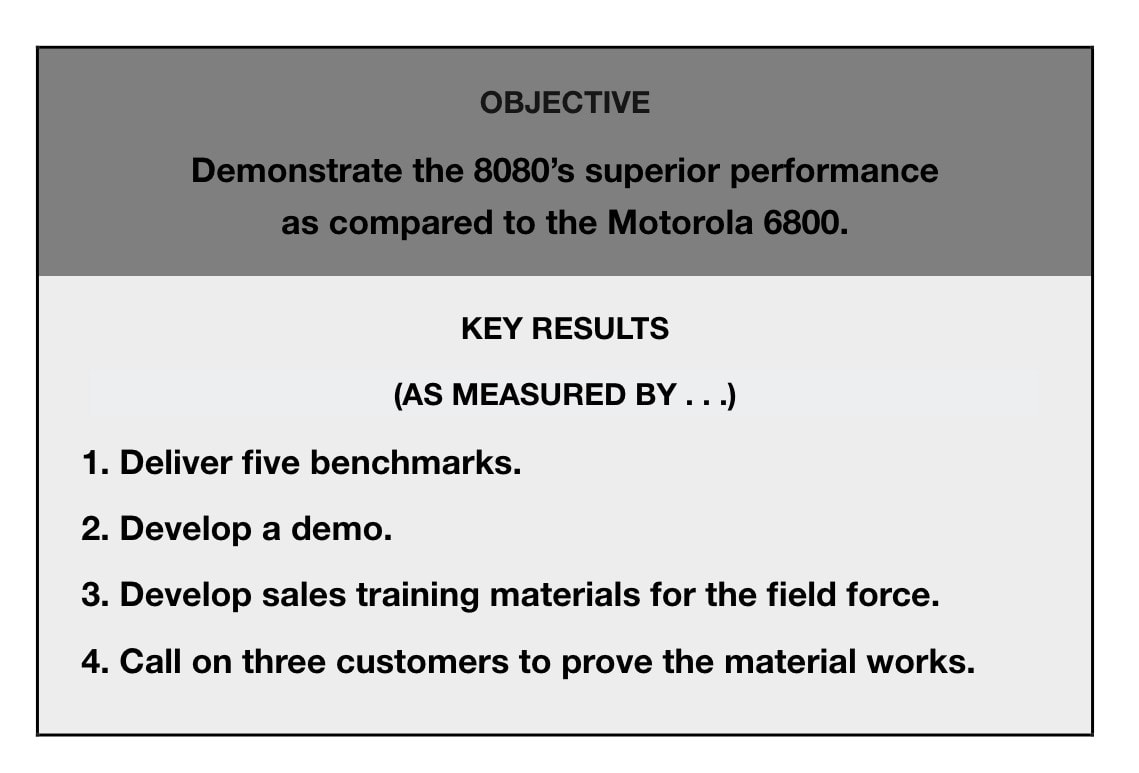

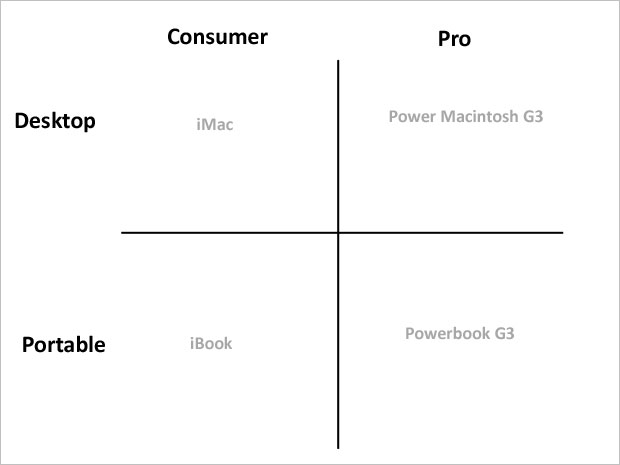

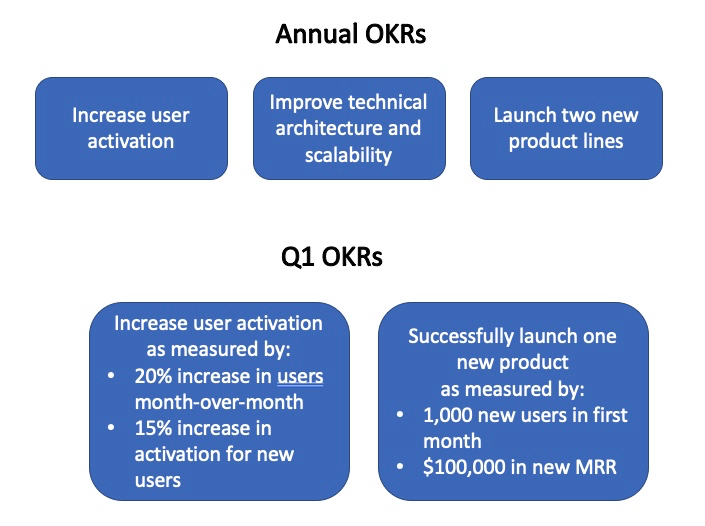

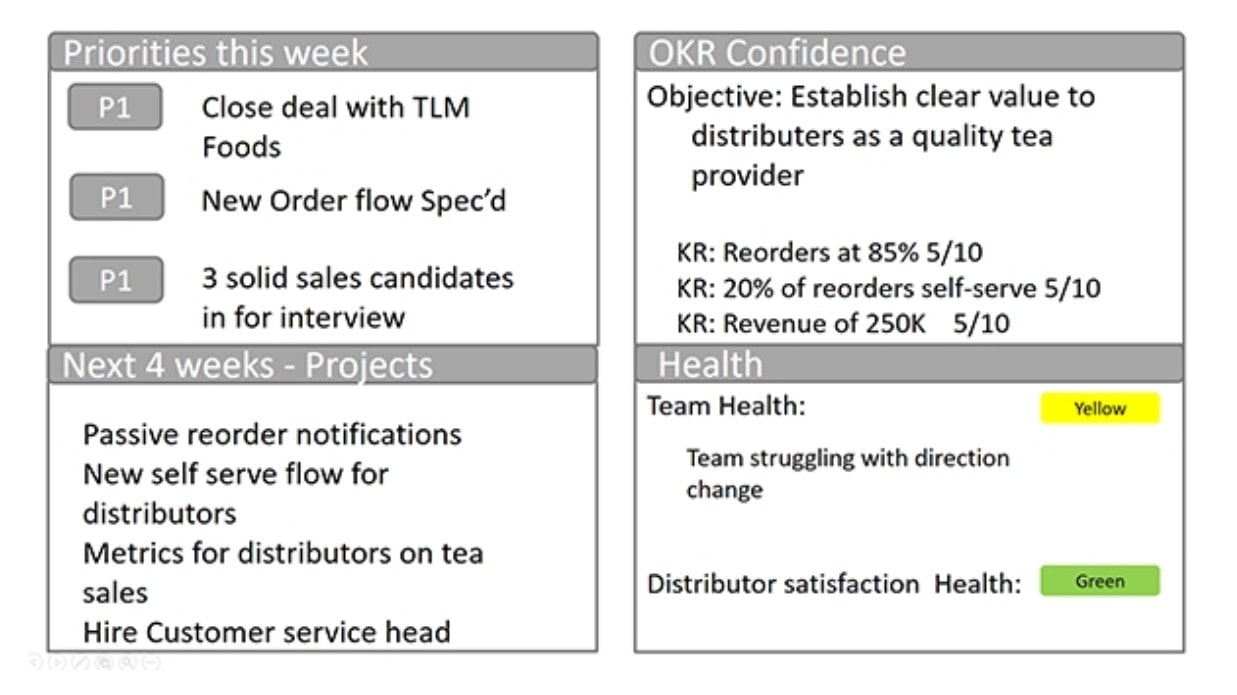

Many of us might not even remember Myspace at this point. Amazingly, in 2008, not even that long ago, Myspace was the top social network platform. While Facebook was rapidly making progress, Twitter was still in its early days, and Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok were still just gleams in the eyes of their founders, Myspace was the place to go. So what happened? Like any story, it’s complex. But one key issue was a lack of product focus. Myspace didn’t know what it wanted to be. You can see that in the image above. Was it a place for friends? A place for music? A place for games or videos? It ended up being a place for everything, and it did none of it well. Myspace didn’t have an obvious idea of what it wanted to be or accomplish, and could never decide on the best way to get there. That’s not surprising. If you don’t know where you’re going, it’s hard to figure out the best path. And within a few years, Facebook dominated social media. Which should never have happened. When you have an existing network, maintaining it should be the simple part. But they weren’t able to do that. And the rest is history. So how can we avoid becoming Myspace? The secret (or not-so-secret) ingredient is to define clearly what you are trying to do — within your company and within your product. Myspace didn’t fail for lack of experimenting, but for lack of clearly defining what they needed to do to be successful and then executing well on those things. A great tool for avoiding this issue is OKRs. I’ve used OKRs in almost every team I’ve been in. There isn’t anything magical about an OKR itself, but the principles and the process make them extremely successful. So let’s take a closer look. A Little OKR History For those unfamiliar, OKR stands for Objective and Key Result. The objective is a high-level, aspirational goal you are trying to achieve, and the key results are how you are going to measure your success. That’s it. They are meant to be collaborative, open, and transparent. They are also meant to push you, your team, and your organization. So they’re not necessarily a good fit for every situation, but more on that soon. We consider Andy Grove the father of the OKR. He created them at Intel in response to the more limited goal management styles that existed at the time, such as MBOs (management by objective) and KPIs (key performance indicators). MBOs were centrally planned and trickled down the hierarchy. Unfortunately, that may still sound familiar. And Grove considered KPIs numbers without a soul. While we still like KPIs in the right context, you can’t push yourself with KPIs alone. John Doerr was a junior employee at Intel during the time of Grove, and he has become a chief advocate of the OKR. Below, you’ll find an example of an early OKR from Intel and John himself: Why use OKRs? If you read Measure What Matters, you’ll become familiar with the four OKR superpowers: focus, align, track, and stretch. Focus The most important feature of an OKR is that it allows you to focus on the most important work. It explicitly calls out what you are focusing on, and by its nature, what you are not focusing on. This is powerful for teams and organizations. You shouldn’t have a laundry list of OKRs. Just like you can’t prioritize every product feature as the most important, you can’t prioritize every initiative or every goal as the most important. You need to focus. Steve Jobs famously said, “innovation means saying no to one thousand things.” And he meant it. When he returned to Apple from his time in the wilderness, he cut their product line down significantly. He focused the company so they could deliver fewer things, but better products as shown below. This became very salient for one of my teams. We had a long list of priorities and had been reordering it for a while. As I introduced the OKR framework, I asked the team to focus on one thing. What was the most important thing to accomplish? It was a change in thinking for many. They were used to changing priorities according to the loudest voice, which would happen every few weeks. We eventually agreed on a key outcome to focus on for the quarter. We’d prioritize all the work around that and deliver. It was difficult in the beginning. I had to remind everyone of our focus, both on the team and outside. But the outcomes were outstanding. Rather than incremental changes over long periods of time, we delivered meaningful change in a quarter. Once the broader organization saw what that kind of focus could do, it wasn’t so hard to sell everyone on the idea from then on. Align OKRs are a tool for empowerment and alignment across a team and organization. Remember the MBOs above? Executives would create objectives and hand them down to employees, who would then be accountable for parts of them. You can probably see multiple problems with that. OKRs are a top-down and bottom-up process. Yes, executives and leaders should have OKRs if your company is using them. And you should be able to see their OKRs. You and your team should also have OKRs, and everyone should see them as well. The purpose is to allow everyone to see what everyone else is working on so we can align up and down and laterally. We talk a lot about the up and down part, but not nearly enough about the lateral alignment. If other product teams have OKRs or goals that impact my group (or vice versa), it’s important we’re aware! Or if marketing or sales have specific objectives that are going to take some work from product and engineering, we should probably collaborate on that! If this sounds like a messy process, you’re right. It is highly collaborative and hands-on. Teams will often spend lots of time working on their goals and objectives, but we need to spend a meaningful amount of time working across groups to align on goals and results. Track If you’ve ever been part of an annual planning process, you’re probably familiar with the weeks or months that go into putting together detailed plans, the meetings and discussions and presentations, and the agonizing over budgets and details. And after it’s all done, everyone quietly puts those plans away for the year until it’s time to revisit them next year. That’s not how OKRs work. It’s probably not how annual planning is meant to work either. We use OKRs to track our progress continuously. And to hold us accountable. I use a Fitbit along with some other health tracking apps. I like to monitor my progress and set goals for myself. I check in regularly with my progress so I can course correct (most often) or celebrate (less often). The same idea applies to OKRs. If you set an OKR at the beginning of a quarter and check in at the end of the quarter, you’ve done it wrong. It’s a good start, but by that time there is nothing you can do. The tracking is best done weekly, checking your progress so you can make actual corrections and take action to achieve your goals by the end of the quarter (or time period). Hopefully, it will also give you a reason to celebrate throughout the quarter. Stretch Finally, we use OKRs to stretch. Don’t use an OKR for something like “keep satisfaction above 90%”. If you’re happy with where you are, that’s not a place for an OKR (more on that later). OKRs should push us, our teams, and our companies to higher heights. If it’s easy, and not without a chance of failure, we’re not stretching enough and it’s not an OKR. I recall an OKR meeting we had where one team laid out their proposed OKRs for the quarter. They sounded reasonable, but nothing about them seemed out of reach. We were still early in the OKR process, and it sounded like the team had taken the work they had planned to do, put it into an OKR format, and was content. It’s not enough to set OKRs for what we know we can do. We need to push ourselves, our teams, and our organizations. Who should use OKRs? You should. Your team should. Your organization should. Every product team I’ve come into hasn’t been using OKRs. Neither has the organization. But you don’t need the entire company to start. I’ve always started with my product teams and product organizations, and the company has come along after. You should start using OKRs wherever you are. If that means starting with yourself, great. What do you want to accomplish? How will you know when you’re successful? If you’re a product manager, create OKRs with your product team. One of the biggest changes I’ve made on every product team (and product organization) is to incorporate OKRs into the process. What do we want to accomplish as a group? How will we know we’re successful? How will that help our company and how can we show it? This will change the conversation for you and your team. It elevates the discussion from the features you’re building to the outcomes you’re driving. And the glorious thing is that you don’t need anyone else to even be using OKRs. Others will see your success and want to adopt them, but you can start right now. Your company should also use OKRs. This one may be out of your control if your company isn’t currently using OKRs, but I’ve helped organizations start using OKRs after introducing them to my teams. And I’ve pushed for them in other places, even when they haven’t been implemented. OKRs may not be the end-all, be-all solution, but they are powerful tools for individuals, teams and companies. And in every situation I’ve seen, groups will be better off using them than not. When to use OKRs?I always start with annual OKRs, or at least annual strategic initiatives and objectives for my teams or organizations or products. It helps me think about the bigger picture of what I’m trying to accomplish and what success will look like as we build up over the course of the year. That’s not to say that I’m married to any specific plan, but it helps to visualize where we’re going. I also tie them up to company level goals or initiatives to ensure that I’m aligned with where my company is going and what we’re focused on. From there, I break down quarterly objectives and key results. Quarterly OKRs are pretty standard, since it is a long enough timeframe to get work done, but also short enough to make course corrections as needed. Besides annual and quarterly OKRs, it makes sense to focus OKRs on product areas that will benefit the most. I’ve alluded to this above, but not every product or initiative will benefit equally from an OKR. In a discussion at a conference, Christina Wodtke gave a splendid example of when to use OKRs based on types of products and where they fit into a BCG matrix. For high growth products, it makes sense to use OKRs to push yourself further with them. But for products that are in maintenance mode, either because you are sun-setting them (dogs) or because they are simply cash cows and you are going to continue to let them do their thing but you don’t expect to grow them, the better course is to monitor them with KPIs. How to use OKRs? Shift To Outcomes Rather than starting with what you want to do, start with what you want to accomplish. Stop talking about features and start talking about outcomes. On my teams, I always try to shift the conversation away from features to the outcomes we want to achieve. Features are the means by which we get there, but a feature may be effective or it may not. We can’t be married to any particular feature. We have to love the problem and the goal, and find a way to achieve it. We also need the flexibility and the space to achieve that goal. This can be a mindset shift for many organizations. I refer to it as product thinking or a product mindset. And it can often take time. Many companies are more accustomed to focusing on a list of features or projects for each team. And possibly setting goals based on that. But that is backwards. I’ve gone through this many times with teams. You may be familiar with it as well. If you start with features or projects, you’re coming at it backwards. You need to start with the objectives. Start with the OKRs! Quarterly OKRs Once you’ve shifted to an OKR style of planning, you must actually implement it. Quarterly OKRs are the most common. If the entire company is starting, it will usually start with leadership teams or department heads and move down. If you are starting with your group, well, it starts with you! Don’t expect it to be easy or smooth. OKRs are difficult and take time. You need to put in time and thought before, and then expect debate and discussion. You should set aside several hours initially for all of this. If you have a large group with lots of OKRs, you may need more. Don’t skip past the discussion and debate. It’s important in shaping the best OKRs. You want to create good goals and good measurements that you and your team can get behind, so take the time to do it right. Regular Cadence In her book, Radical Focus, Christina Wodtke gave the simple matrix below to show how to implement OKRs effectively into your weekly cadence. Each Monday you should review your OKRs (the fewer, the better) and how things are progressing. You should check in on your priorities for the week in order to achieve your goals with your objective, and anything you need to do in the next month. And your health check are the KPIs or metrics that you don’t want to let slip as you reach toward your bigger goals. The key is to make the check-in part of your weekly cadence. Start Monday with what needs to be done and end Friday with how things went. It is critical to success, and harder than it seems. Common OKR mistakes

Too many OKRs or key results I recall one leadership meeting I narrowed my OKRs down to three. I had more critical things I wanted to focus on, but more than that would be too many things to focus on in my opinion. OKRs were new to the company though, and not everyone shared my opinion. So some leaders came in with eight or nine OKRs. And we debated. Everything they had on their list was important. And I left some important things off of mine. Who was right? I didn’t budge. I knew if I added more than three objectives I’d take too much focus away from what was important. And I wanted my team to focus. Fortunately, we agreed focus was more important than including everything, though I still think that some lists remained too long. If you have too many objectives or key results, you can’t focus on what is important. The fewer objectives and key results you have, the better you focus on what is important. The more you and your team can rally around the goal. And you can more easily say no to things that distract you from your mission. If everything is an OKR, nothing is. Tasks as key results Another mistake I’ve seen frequently is making your task list into your key results. For me, this results from having an output as an objective rather than an outcome. In one example, the objective was something like “replace all the old phones”. Then the key results were a list of milestones like “order new phones”, “replace phones in area one”, “replace phones in area two”, etc. Your OKR shouldn’t be a task list. It shouldn’t be a maintenance item. OKRs are about driving meaningful change for your business and your users. Why are you replacing phones? What impact should it have? How can you measure it? And if you don’t have a good way of measuring it, should you find one? Lots of areas need better measurements, and OKRs can be a good way of shedding light on that. And if that’s not the case, should you be using an OKR here at all? Never reviewing It’s so easy to set goals and never review them. We create a plan and then never revisit it. We simply hope for the best. OKRs are meant to help us track our progress. And not just quarter to quarter, though that is an improvement over the annual planning process. We should track progress continually. We talked about it above. Including OKRs in our weekly planning process is critical to their success. I’ve found the most success including OKR status checks into existing team meetings. If you are part of a scrum team, you likely have bi-weekly meetings at the beginning and ending of sprints. Those are excellent times to review sprint goals and OKR statuses. If you are part of a larger team, you probably have some weekly meeting or bi-weekly (fortnightly) meeting. Add OKR status reviews to those meetings. Check progress and see how things are going. Trying to copy XYZ company No two companies are the same. I’ve used OKRs at multiple companies now and every company does them differently. Google does them in Google’s own style. You don’t need to be Google. Be your own company. Find your rhythm. You will flounder for a bit. But you will find the style unique to your organization. Learn from the books and articles and things that others have done. Learn from others who have used OKRs in other places. And then take all of that and don’t feel bad for not being perfect. That’s not to say you shouldn’t try to be good at OKRs or use good principles, but you don’t need to be Google or Intel. OKRs aren’t a silver bullet, but they are a great tool to empower teams and change the mindset of your organization. Rather than focusing on features, they help you focus on the outcomes you want to achieve, and empower the groups and organizations to achieve those outcomes. They take some practice, and will require giving up some centralized control, but the results will be better outcomes for your business, your users, and your employees. |

AuthorMy personal musings on a variety of topics. Categories

All

Archives

January 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed