|

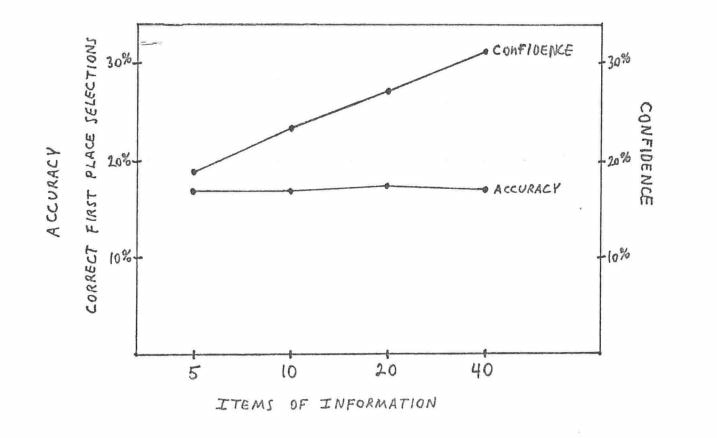

In our current day and age, we are constantly bombarded with new information. It is more accessible than ever before, and we’re constantly awash in data, metrics, news, reports, etc. How much of it is truly valuable though? How much of what is around us every day is truly an actionable signal versus what is just noise? It’s hard enough to answer some of these questions in our day-to-day lives. It can become even more difficult as a product manager as you’ve instrumented your products and are constantly paying close attention to the huge variety of metrics that are available to us. From latency to active users to monthly revenue to everything else. There is a lot of information available. But what is most valuable? And over what time period? And who decides? Financial Markets I spent a good deal of my early career in financial markets. There probably isn’t a better example of data overload than in finance. The sheer volume of data available is astounding. And the pace at which you can get it is overwhelming. New reports are available every day with economic indicators, financial forecasts, analyst rating, price movements, and much more. And add the fact that CNBC is on all day long, you have the perfect recipe for information overload. So how can you make sense of all of that information? How do you trade on it? The short answer is that you don’t. You simply can’t. If you tried to, you’d be thrashed around hour by hour and end up losing significant amounts of money. While I never traded professionally (for better or worse), most good traders I had the opportunity to work closely with had key pieces of information they’d use. A way to separate out the signal from the noise. A way to create an investment thesis using key pieces of information that actually move the needle, and then make adjustments based on additional inputs they’d get. Whether that is certain ratios for stocks, or certain spreads and purchasing patterns for bonds, there are some key signals that stand out from the noise and can give real insight into markets. We’re Not Great at Separating Signals from Noise Despite knowing this, we all fall victim to overconfidence based on noise. In a fascinating study done by Paul Slovic (and described really well by Adam Robinson in a podcast found here), a group of professional horse race handicappers were gathered to see how well they could predict outcomes based on a number of factors. At first, they were only allowed to pick 5 pieces of key information about the horses and then were asked to make their predictions. Using just the 5 key things they knew, they were able to correctly predict nearly 20% of the time, which is well above what we would expect from chance. They were also roughly 20% confident in their predictions. Not bad. The key part of the study came as more information was added. Each handicapper was allowed to pick more and more data. As they did, their confidence in their predictions increased while their actual results stayed roughly the same. Despite knowing more information, they were not able to better predict the outcomes, though their confidence nearly doubled. More Information Isn’t Necessarily Better I’ve been asked throughout my product experience to put together numerous slide decks and reports with significant amounts of data about our products. Our team is often asked the same. Numerous charts with all the information about our applications that people feel is relevant to see and understand. The specific metrics of interest often vary depending on the manager and what they care most about (often based on their background or experience). But there are always numerous problems with this. First, by paying attention to every metric or piece of information, we’re essentially paying attention to nothing. The true signals get lost in the noise. In a multiple page dashboard of metrics, what are the important things? CNBC has to fill up an entire day with reporting and information. That doesn’t mean that it’s meaningful. There are probably days when nothing should be reported because it’s all noise. But that’s not how the world works. We may be asked to fill out a whole host of metrics for our products. But that may not be the right thing either. Second, we end up focusing on the wrong things. Often in reports or slide decks, the main things that get attention can be the wrong things. For example, if a specific metric isn’t great or isn’t known well, it can get an outsize amount of attention. We may then focus our attention on making that metric better simply because its lack of information got the attention of upper-level management, when it is likely not significant overall. Third, we can get into data paralysis. By requiring more and more data before we make a decision, we may never end up making a decision at all. One of my teams nearly had this happen to us with an executive who wanted to analyze (nearly to death) a vendor selection. He required months of work and literally dozens of pages of analysis for what amounted to a relatively insignificant decision. In the end, the decision was made by inertia since we had already selected a vendor to pilot with, and it became too late to make any changes anyway. Finally, on the flip side of paralysis, we can fall victim to overconfidence. Like the study above, we feel like with all the information available we have a good handle on things. Pages and pages of data must mean that we can be 100% confident, right? It’s that kind of overconfidence in the data that can lead to catastrophic outcomes. Because rather than understanding that we may only be 50% confident in an outcome and manage it accordingly, we go in with 100% confidence and are unprepared for the unexpected. Does that mean we shouldn’t care about our data or metrics? Should we not instrument our products? Of course not. We need data and metrics. But we have to make sure we’re making decisions and doing work based on the most important metrics. What Can We Do? So given the pitfalls above, what can we do? First, we have to understand our biases. I was on a bit of a psychology kick a few months ago, and my reading included some great books including Behave and You Are Not So Smart. It is fascinating to me to analyze our own thinking and understand some of the areas where we may fall victim. For example, the latter book dives into a number of fallacies we may commit. One is finding too many patterns in randomness. It happens more then we think, especially with all the data we have. And we can start to correlate unrelated data points, leading to potential wrong conclusions. But when we understand where the pitfalls are, we can at least acknowledge them, if not avoid them. We can see when we risk being more tuned into the noise. Second, we have to elevate the important. Not every metric is equal or even important. We have to help key stakeholders and managers understand that. Be confident as a product manager! (More on that soon.) You know your product. You know the important things. While certain stakeholders may want to see certain metrics based on their background or point of view or department, we have to ensure that those metrics don’t take the place of the really important ones. In order to help with that, it is great to explicitly establish what is important and why. A great way to do that is with OKRs (objectives and key results), which I’m a big fan of. (Check out Measure What Matters or Radical Focus for some good reading on OKRs). By calling out the key things our teams are focused on, we can avoid getting sidetracked with other things. Earlier this year I made a concerted effort to do this for our product. While there are many metrics we’d like to move and that are important, by calling out one, and only one, we’ve been able to keep the focus on the main goal. And while we don’t want certain other indicators to slip, when we have to make a trade-off, it is clear to everyone what we’ll do. And that’s the point. Trade-offs will always have to be made in product development. But having a clear goal or objective allows us to make those trade-offs. If we had 15 metrics that were all equal, we would constantly be pulled in the direction of the loudest metric (or voice) at the time. And that’s no way to do product development. Finally, we have to accept that data don’t make decisions. Signals have to be interpreted, and there is inherently a human element to that. No matter how much data we have, it cannot make a decision for us, nor should it. Understanding the most important things, synthesizing that information, and determining actionable steps can be just as much art as it is science. There is an ever-increasing amount of noise all around us. From metrics to voices to everything else, it is increasingly difficult to identify the important. It takes a deliberate effort to not only understand what is truly a signal, but then to ensure that we aren’t getting lost in the sea of noise. It’s an artful balancing act, especially in product development. But that’s part of what makes it so exciting and fun.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy personal musings on a variety of topics. Categories

All

Archives

January 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed